Eva Louisa Jonas is a visual artist, facilitator and co-founder of art platform UnderExposed. She lives and works in Brighton, UK.

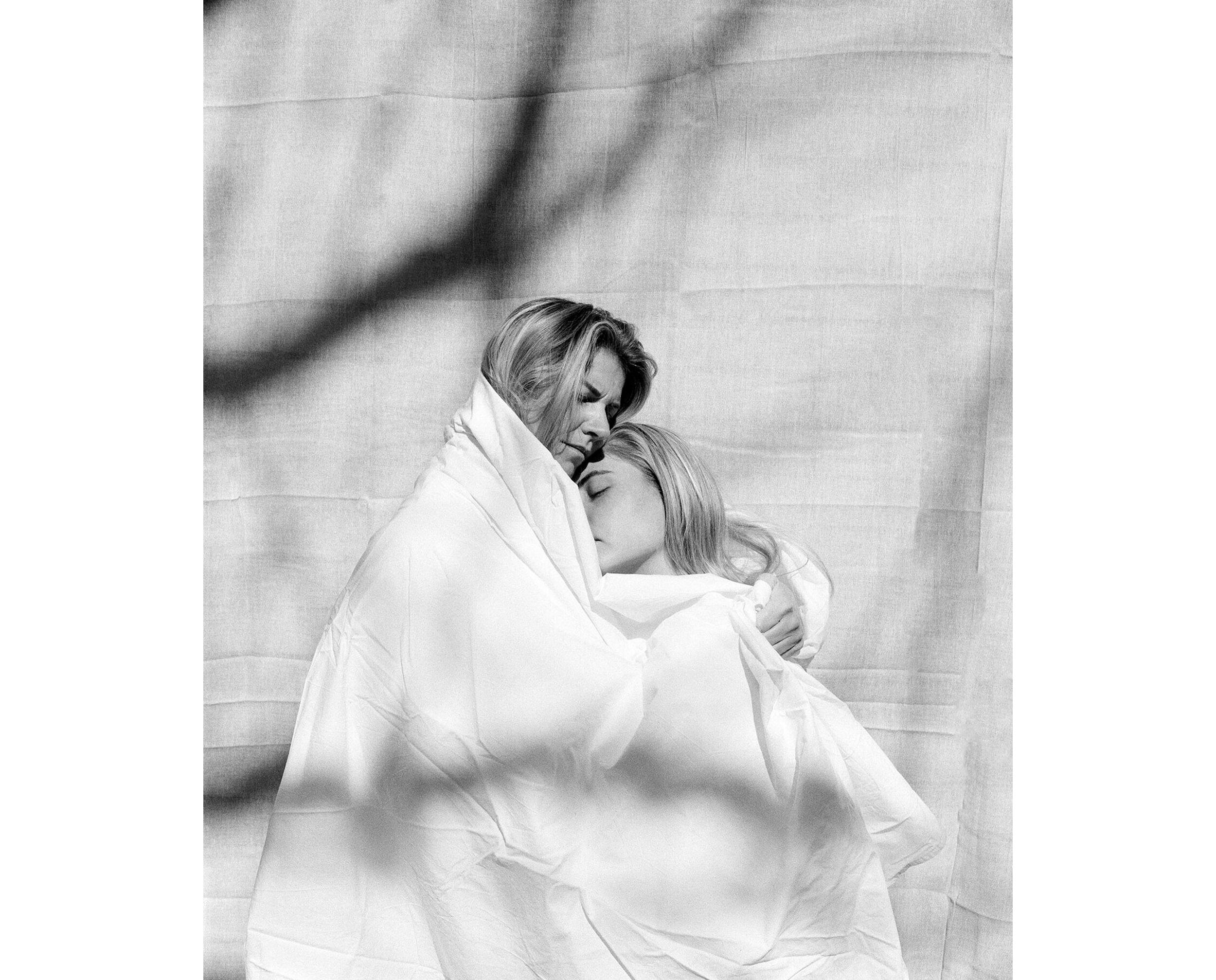

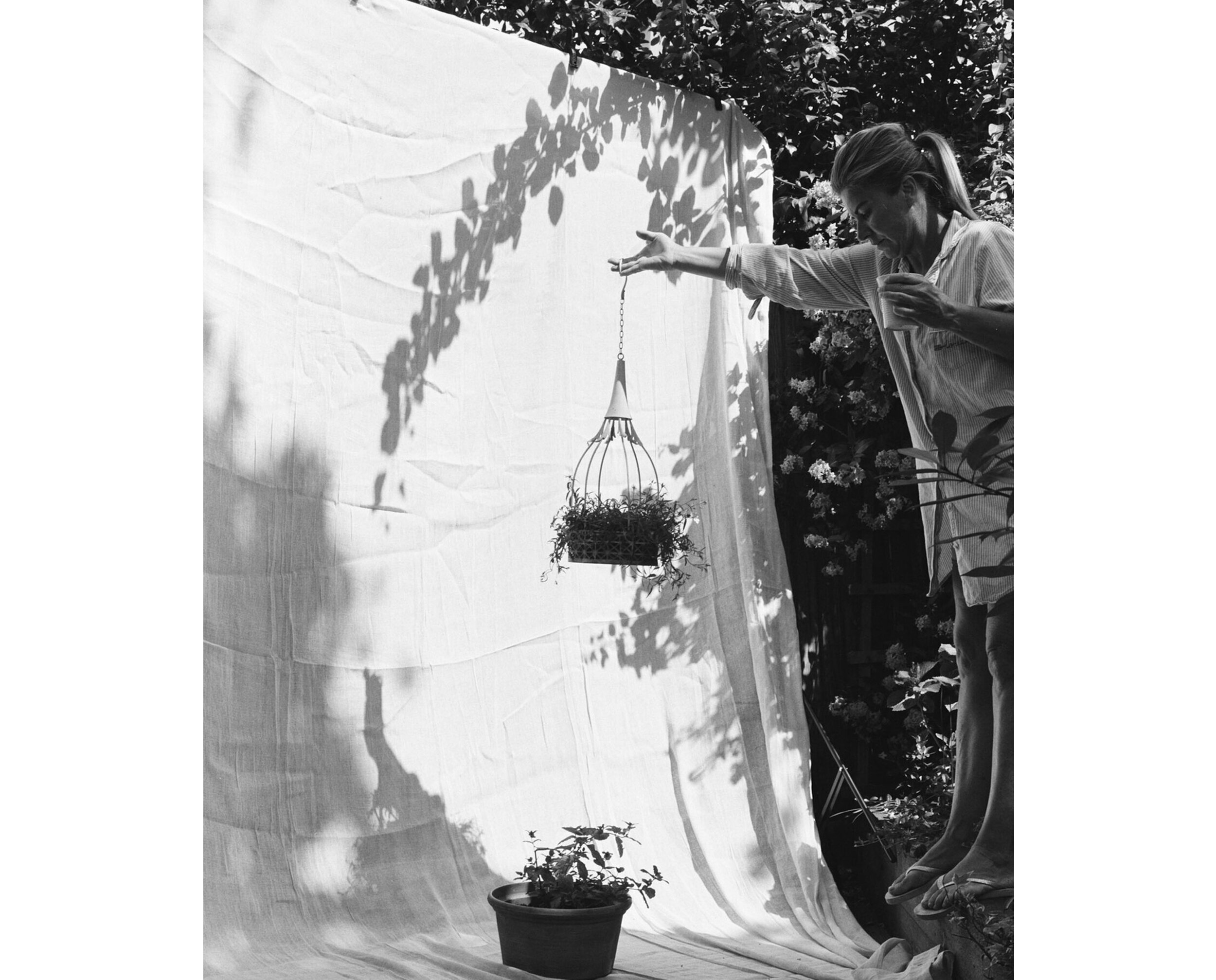

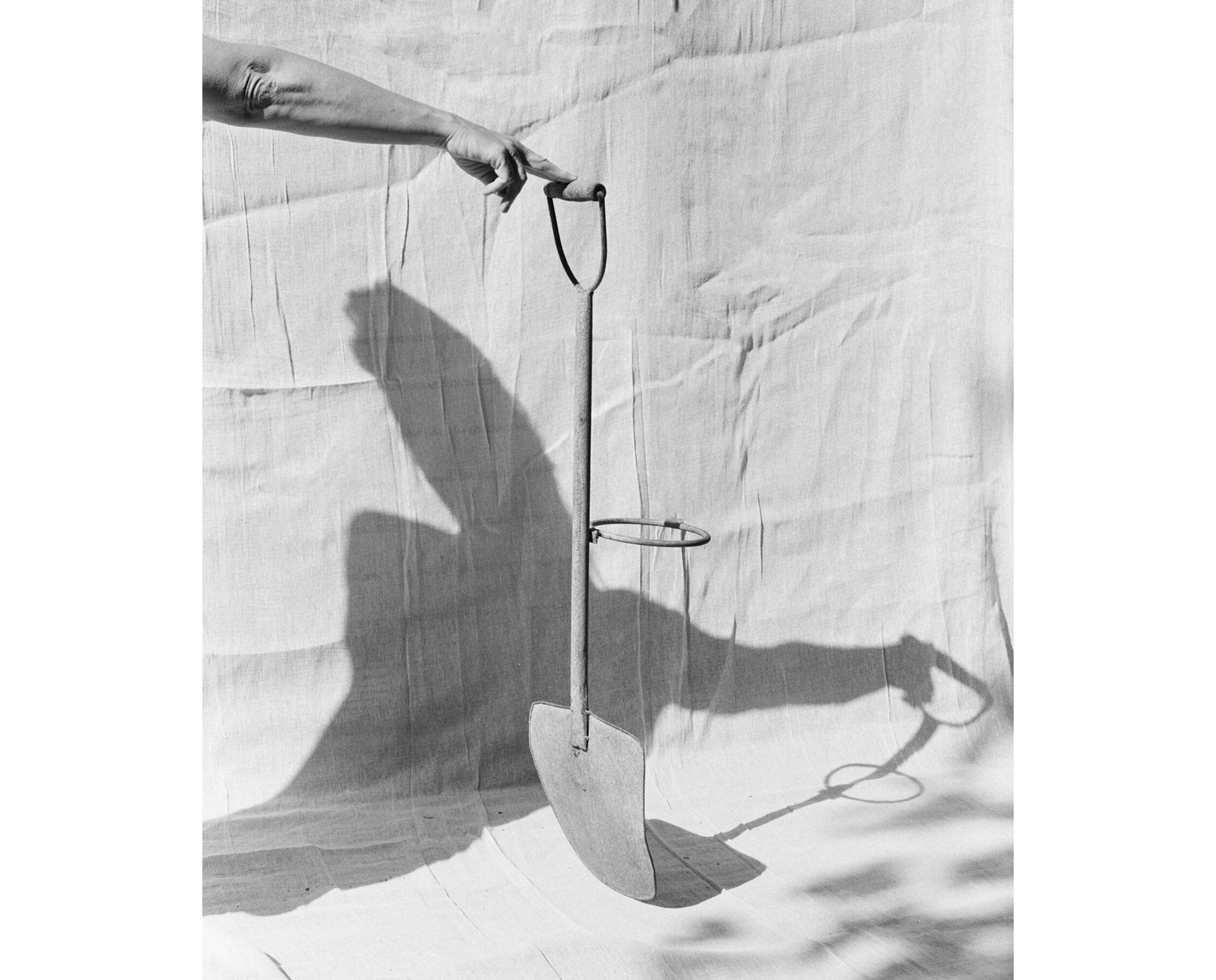

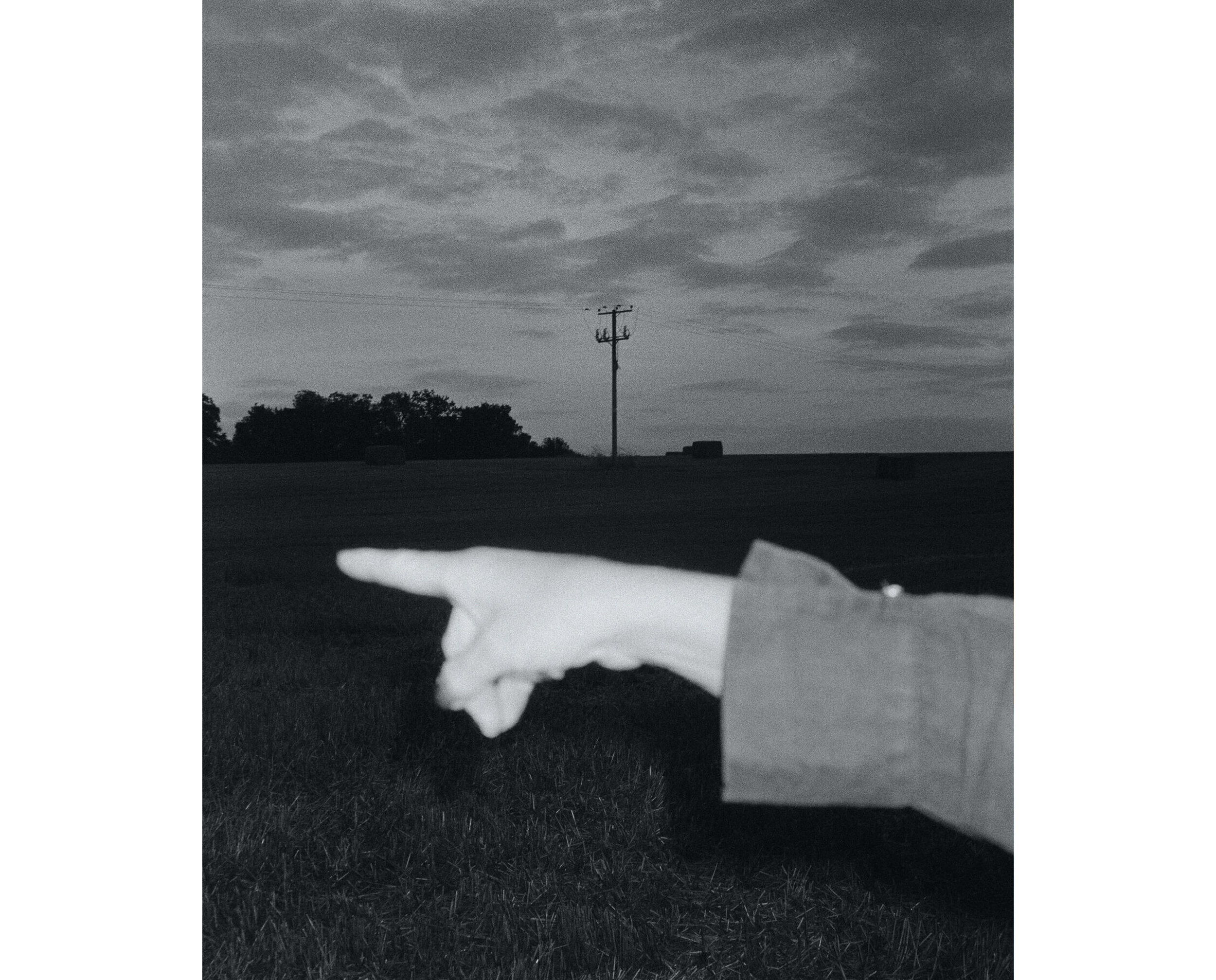

Her practice involves “building photographic narrative through construction and material; forms at rest or manipulated, influenced by our habitual and gestural environments”.

Let’s Sketch the Lay of the Land is available to purchase in the Unveil’d shop.

Interview by Tom Skinner

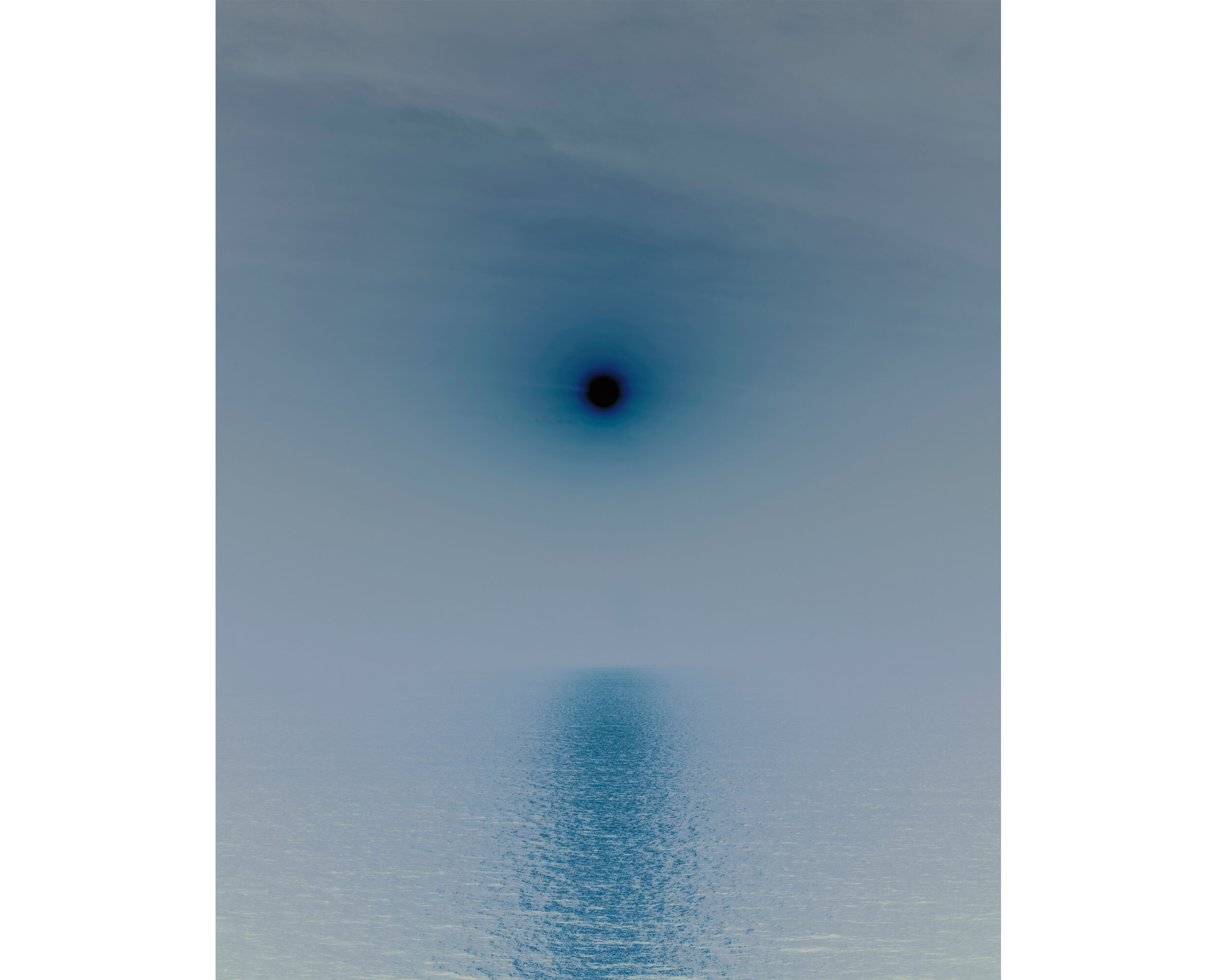

TS: Throughout your photographic works, there is a sense that connections between landscape, personhood and materiality are explored in a sublime and slightly ethereal way. Do you feel that Let’s Sketch the Lay of the Land continues to explore these themes, or does it depart from them in any way?

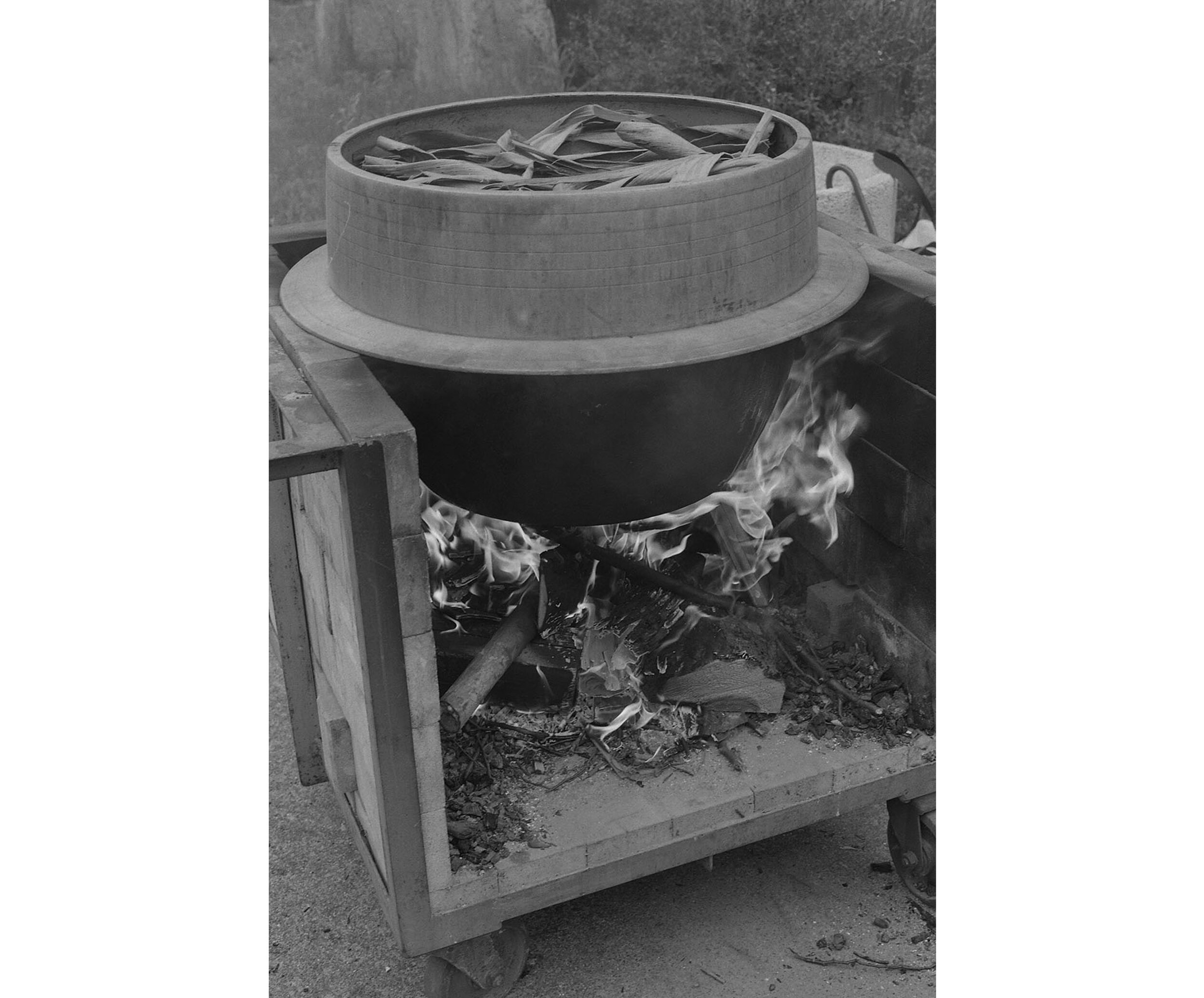

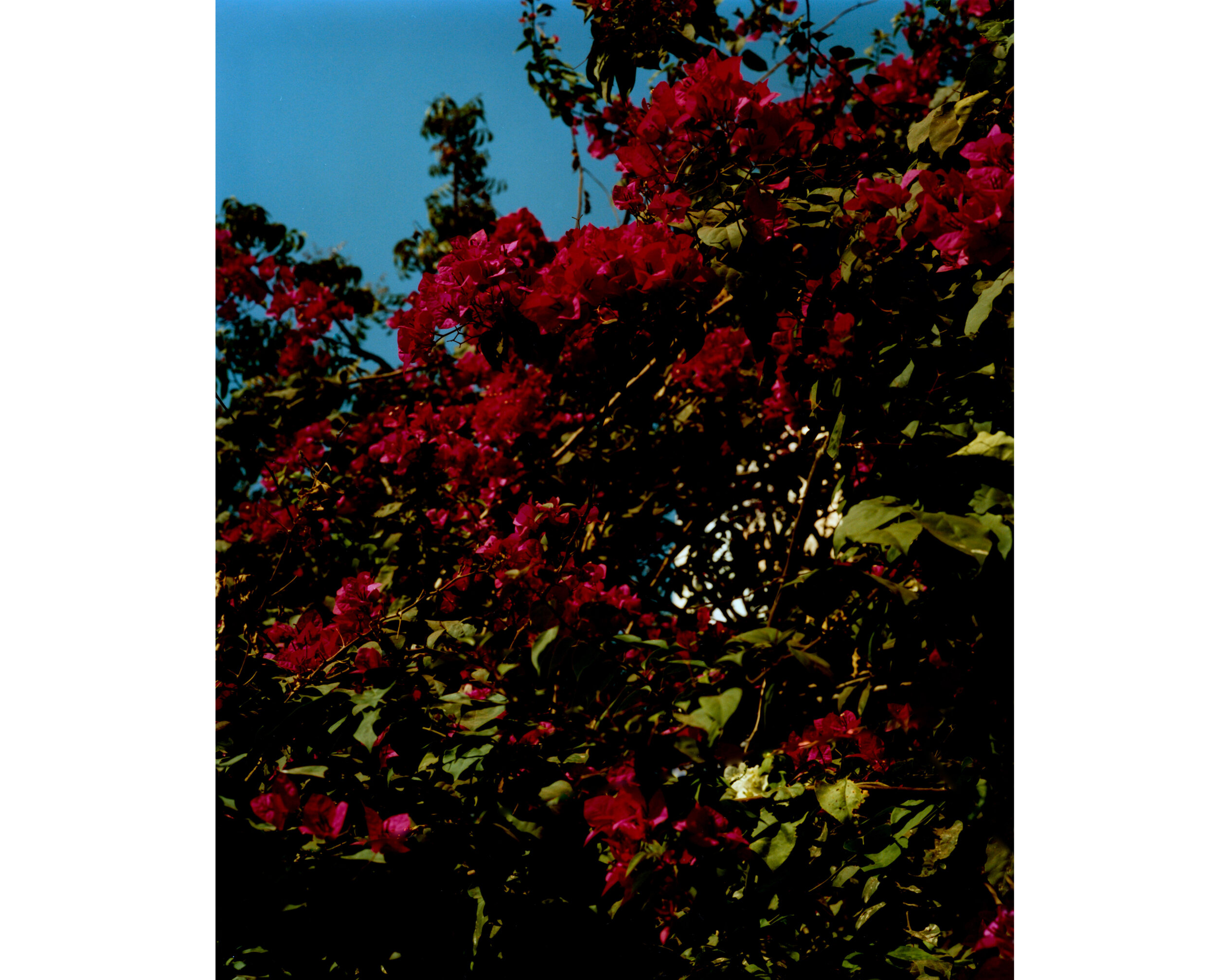

ELJ: Let’s Sketch most definitely continues to explore these themes – in early conversations with September Books it was clear the images in the book were going to be taken from numerous bodies of work (and my image archive) and what formed was a kind of visual research and exchange between gesture, material and form.

It was so exciting to be able to use the book’s format to explore this, working outside of individual ‘projects’ and into something that mediated my approach to image making - the exploration of simple materials and the collected words and phrases that resonated along the way.

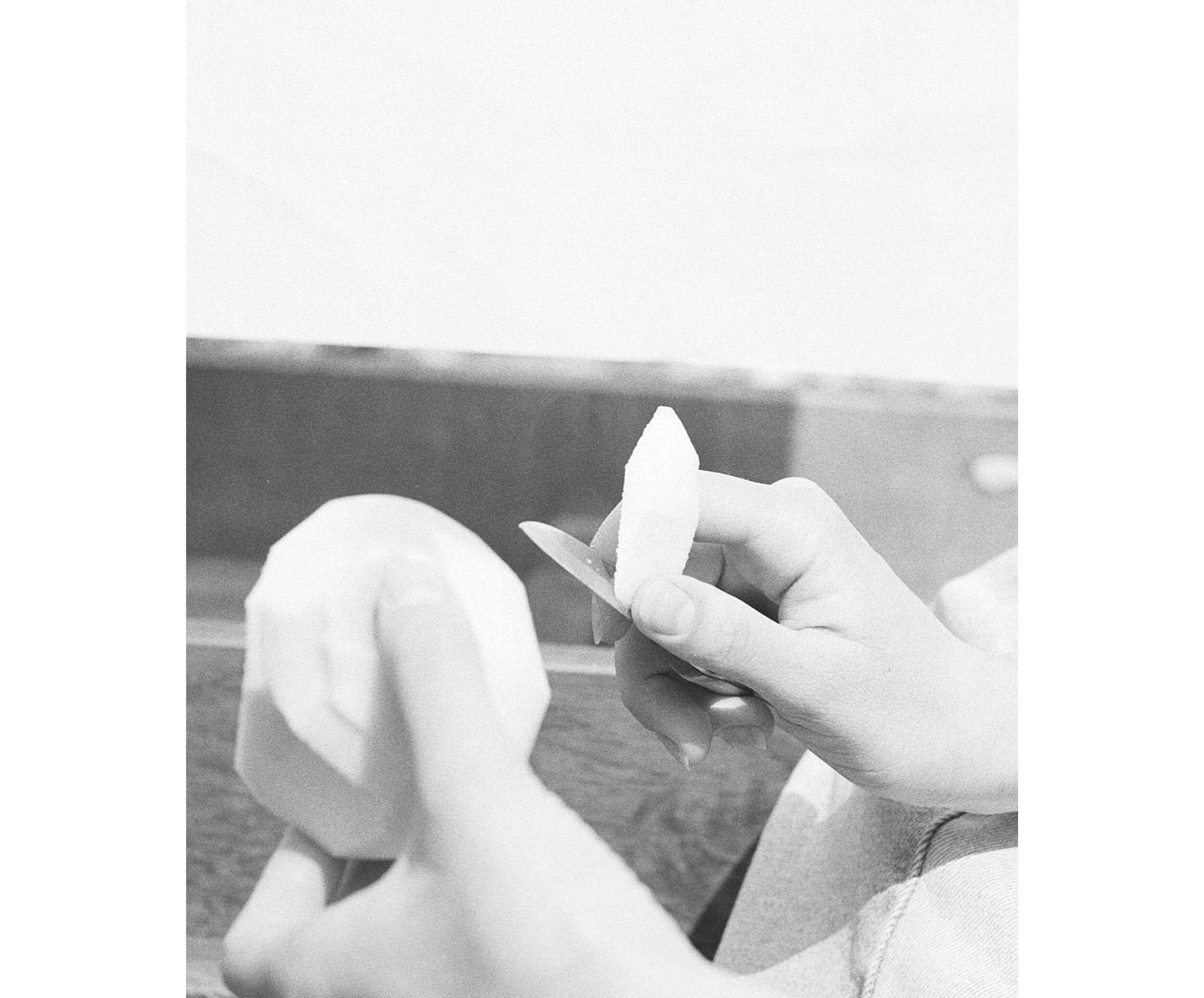

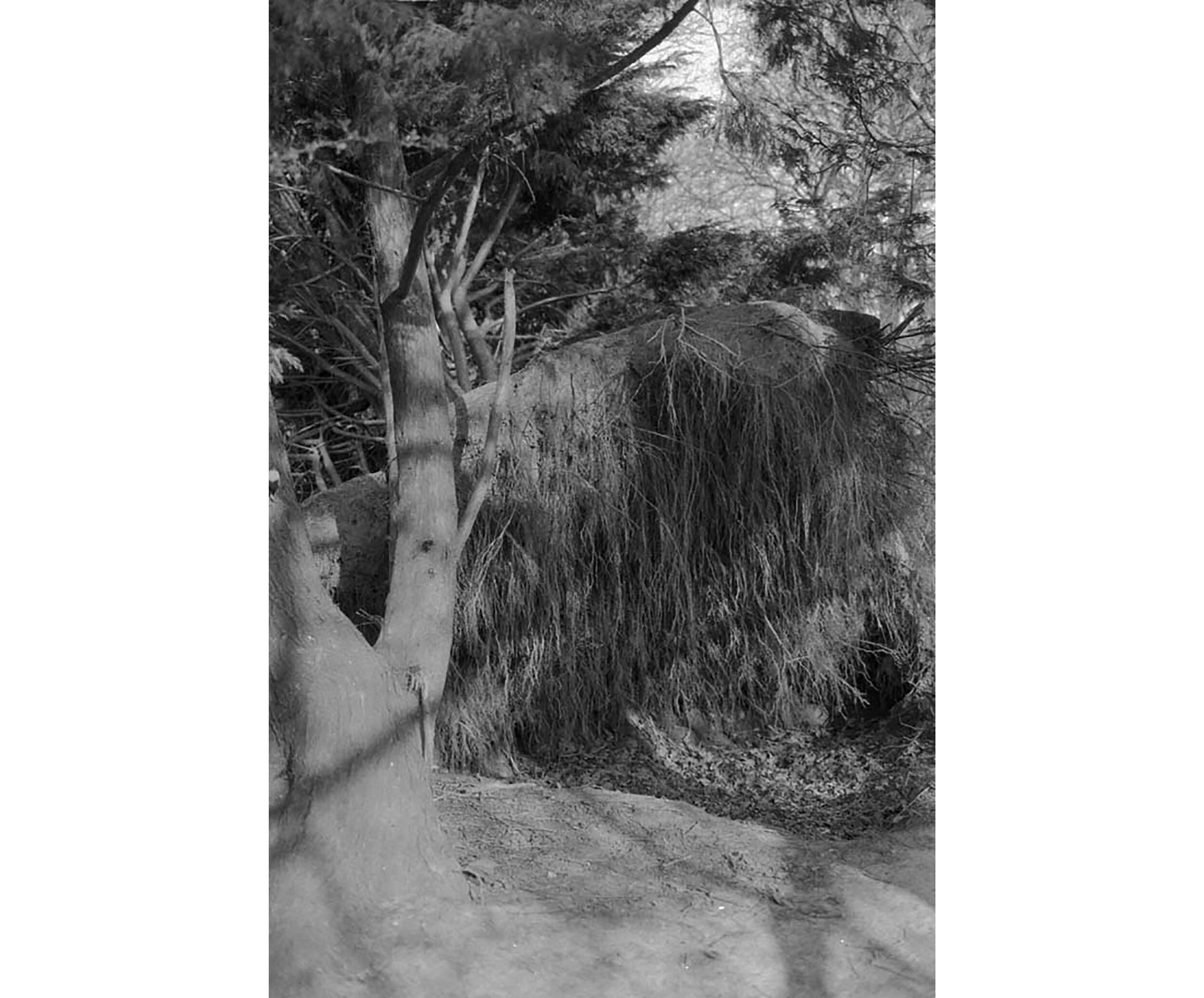

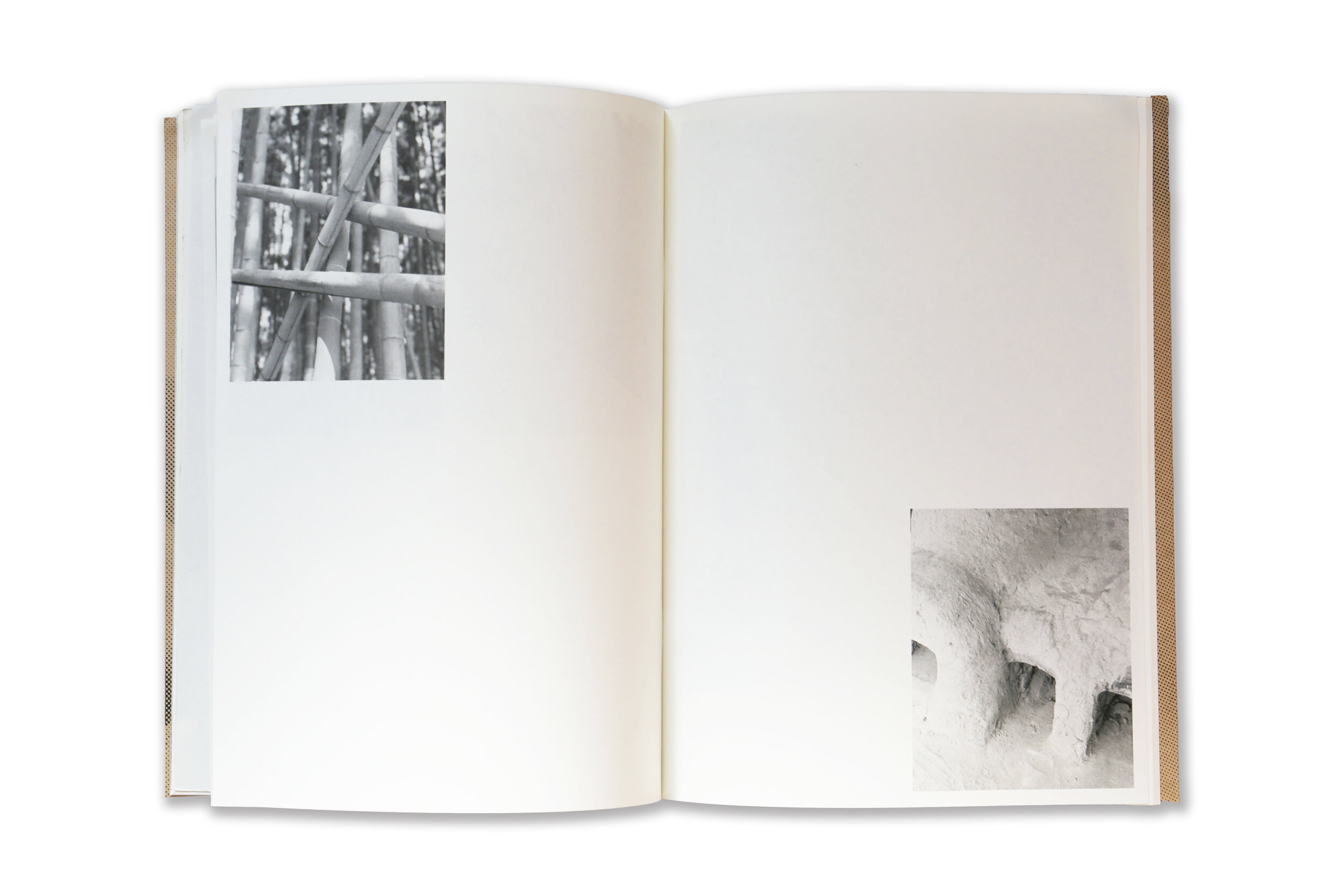

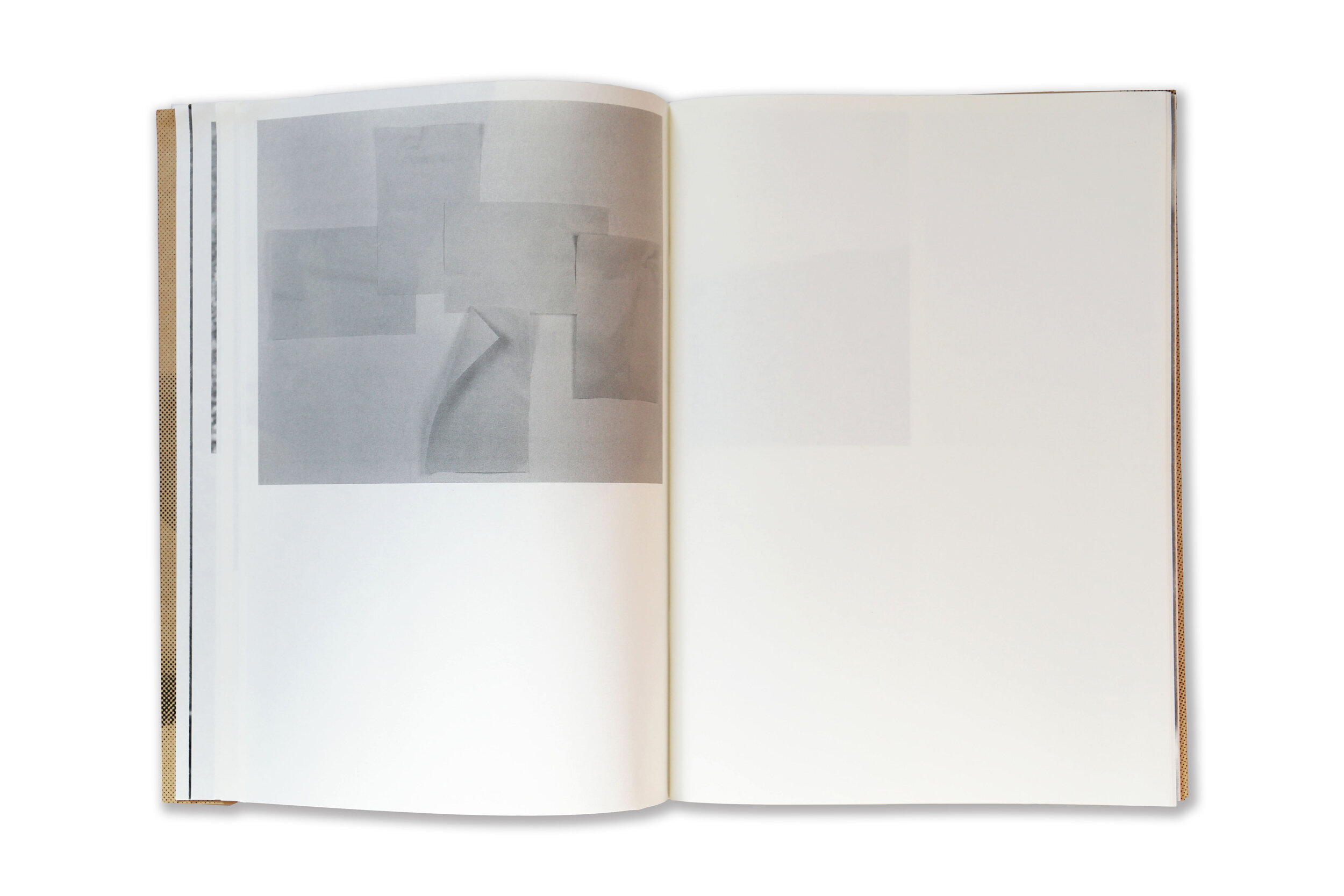

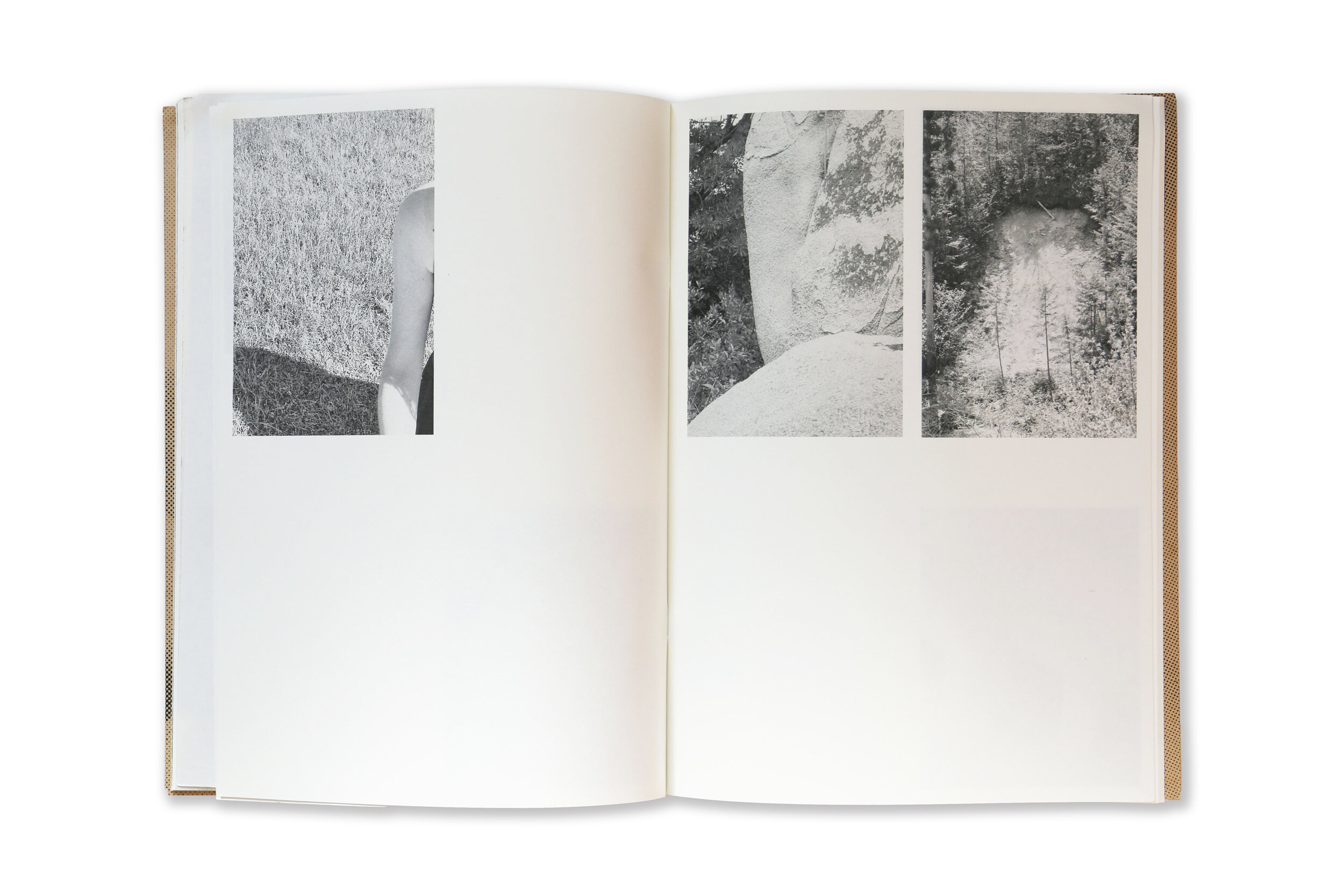

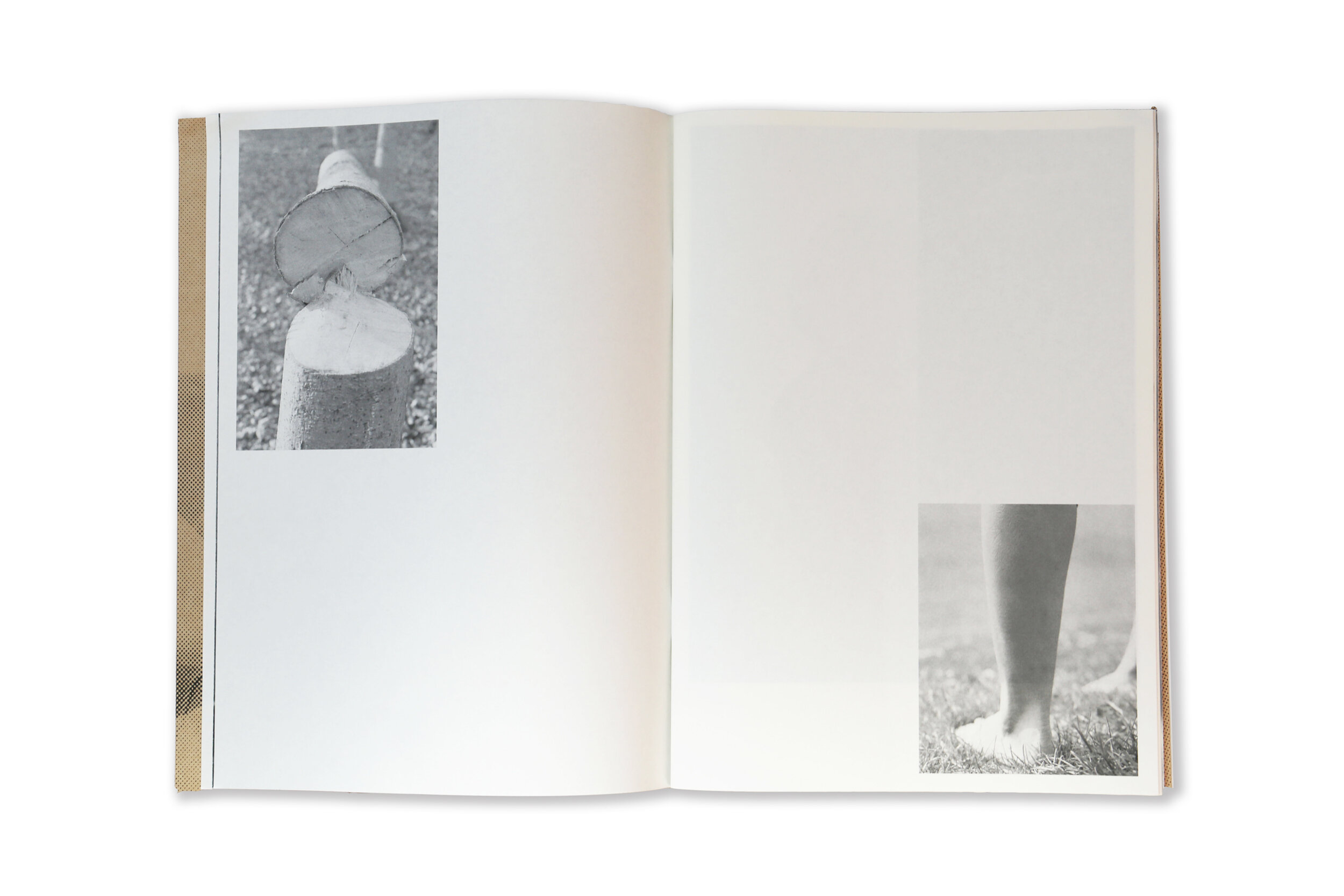

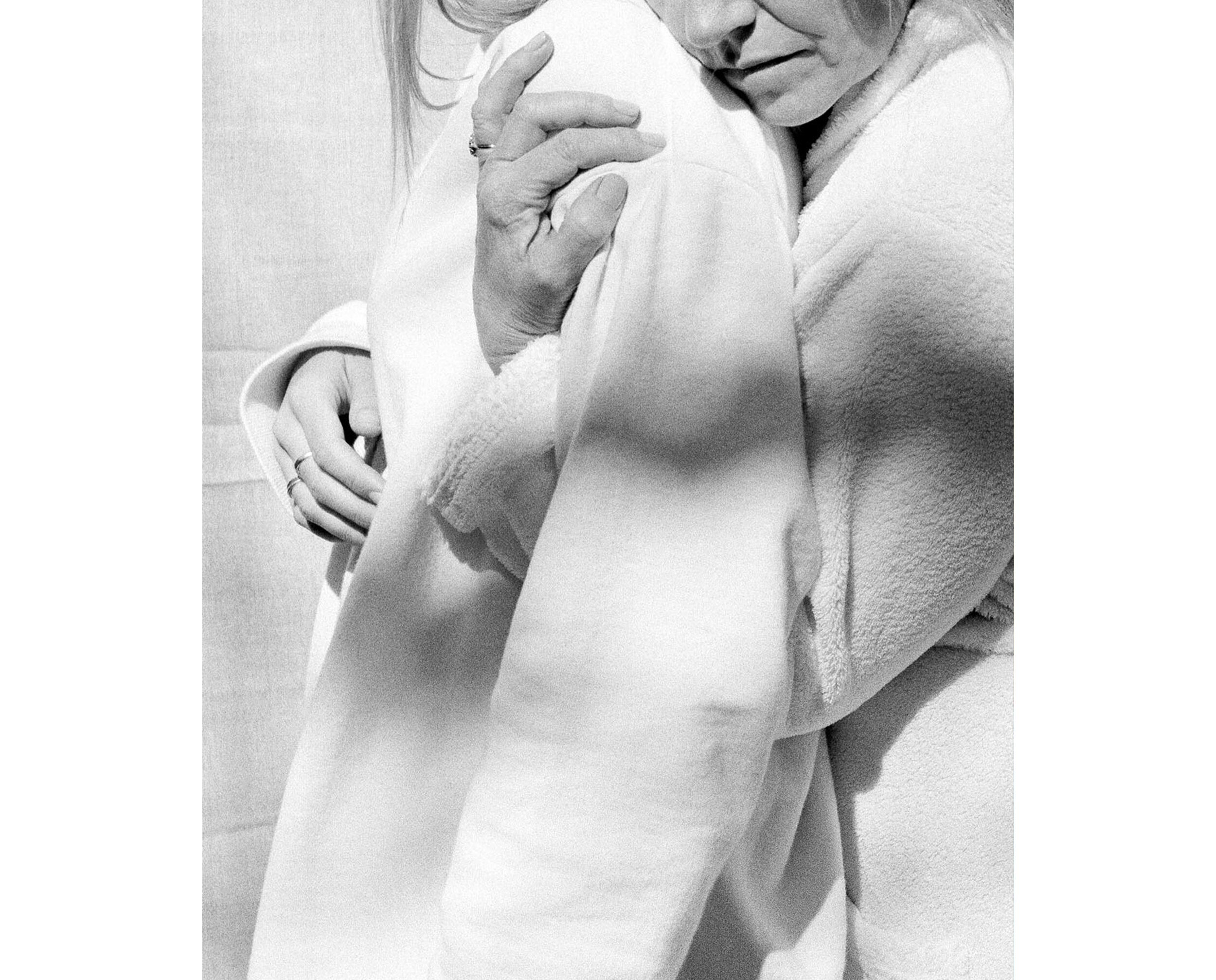

TS: Within the book, there appears to be a series of fractures; a tree which has been felled, folded paper, an interaction with a creased tarpaulin. There are also parts of the body which have been ‘fractured’ by the camera, abstracted and cut out of frame. What draws you to abstract the subjects and make these connections?

ELJ: Initially I thought that the work was about coming to some conclusion, some understanding, an end - as if something was going to reveal itself to me about picture making, the landscapes, materials and creative intuition as a whole, but for me the very nature of the work and process means this wasn’t the case.

In a way these fractures don’t exist on their own but in relation to one another, as an eventual whole, and the abstraction is part of this. By including images that emphasise the handling of objects, of gestures and movement in landscapes, for me contributed to this building of something whole.

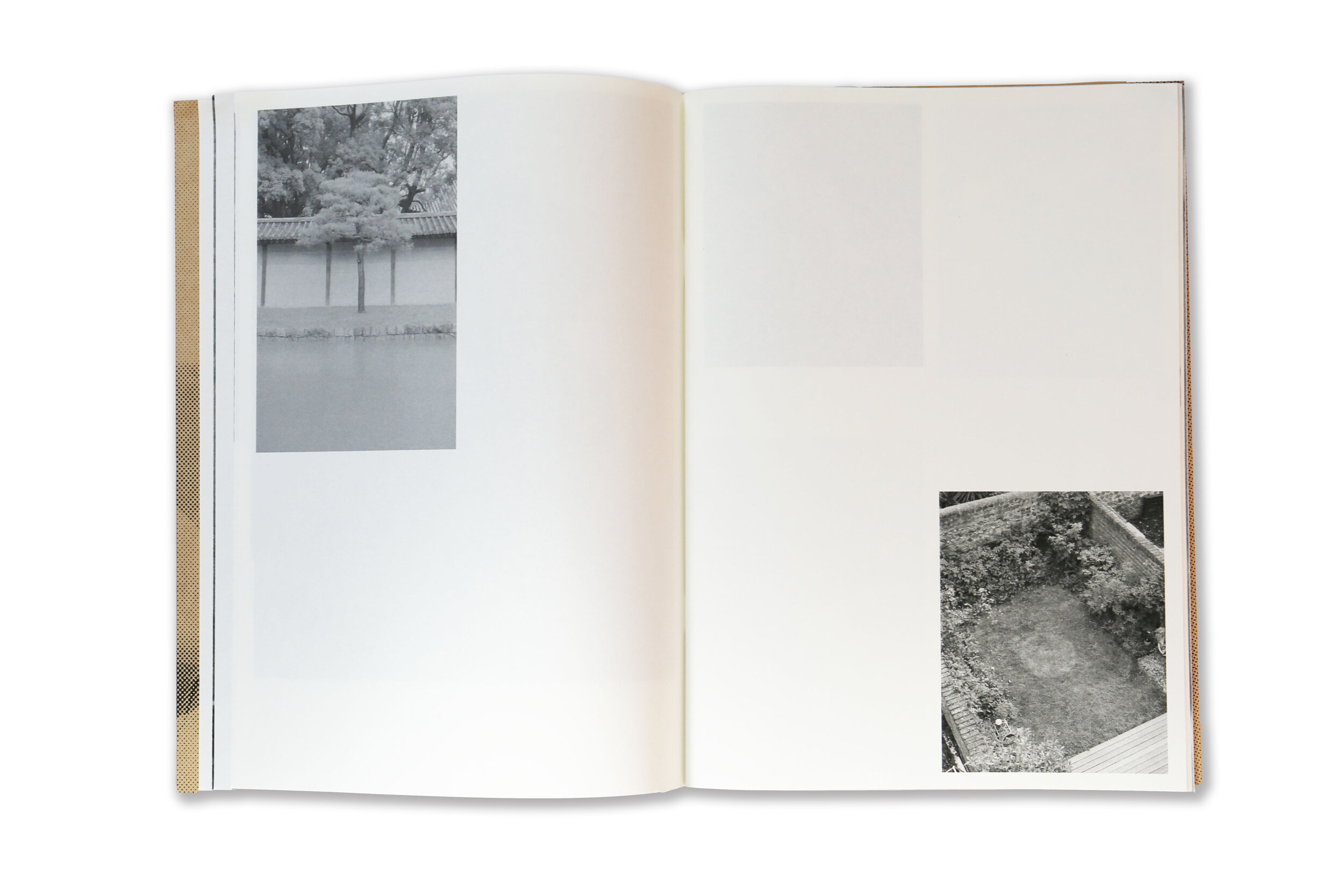

This could be quite taken literally too with the way the photographs converse with each other on a spread and the connections and associations that are formed. A lot of the book’s overall sequencing was considered around this.

TS: This is your first book published by September Books, before this came a dummy titled That Thing Over There and a beautiful handmade book Fulgurite, which used Japanese stab-binding. What is your relationship with photobooks and print making?

ELJ: Working off screen and with physical prints is definitely the first part of my process, this could be Silver Gelatin prints or quick cartridge paper prints from my home printer, this is why I’ve gravitated towards photobooks, you have to engage with something on a material level and its often far more accessible than an exhibition, in price and locality – they are portable.

I’ve always been interested in different paper stocks, scales and finishes and how this can change the direction of the work – Fulgurite in a way was as much about the Awagami Paper, its deckled edge and size and stab bind as it was the actual images. I completed a Book Arts module in Uni and have made my own paper in the past so it’s been something I always consider early on in my process – it’s fun and I can engage more in the ‘making’.

I definitely brought this approach to Let’s Sketch the Lay of the Land, early conversations with September Books were around paper stock and its colour - before sequencing or edit. We decided on a 90gsm Munken Cream Paper which allowed for the show through of images, this was really important as it created an exchange between partially visible photographs.

TS: The book ends with a series of disjointed phrases, which allude to the possible meanings of the images while also stepping away from them; ‘not thinking, just feeling’. How does writing and text inform your working process?

ELJ: In Let’s Sketch I knew I wanted to include some text in the book but a formal, paragraphed text felt like a bit of a betrayal of the book, what related more to the body of work was what came to be the text collages. This was the fragmentary text on the final page, as for me it behaved more like images, in the way they are in placed and moved, and related to one another. They were taken from a few years of saved phrases and words that always came up in my practice, I found myself always being reminded of them, either through reading or looking through old notebooks.

I’d initially used text in this way for my title page in ‘That Thing Over There that surrounds and sustains us’, I did this really intuitively and just felt it resonated with the way you read the title out loud. I suppose the same can be said for the way I use text in my overall practice, naturally gathering words and phrases that resonate with the images I am making, their meaning and significance only fully realized when read aloud or placed all together.

TS: The final piece of text is ‘Being lined up just right, five children describe feeling centred from Awareness Activities for Children, 1975’. What was this study about? It reminds me of similar child studies of the seventies which explored play and the negative effects of toys. The idea was that learning and imagination were improved if children didn’t have toys and instead were encouraged to build their own. There is a sense of this playfulness and collaboration throughout your book and I wonder whether this connects with you at all?

ELJ: The focus wasn’t so much on the study and what it entailed in a literal sense, rather earlier ideas around the images and my making revealing something to me as I came to end of the book.

Children describing what feeling centred feels like as ‘Being lined up just right’ to me vocalises a simple and playful way to be in the world – something as adults we need to connect with more, perhaps? I do, anyway.

Playfulness and collaboration definitely connect with me, throughout the book images of materials and human interaction with them appear - they acted as playful points of rest and reflection, a nod to my participation in the image making and as a reminder to carry on in such a way!