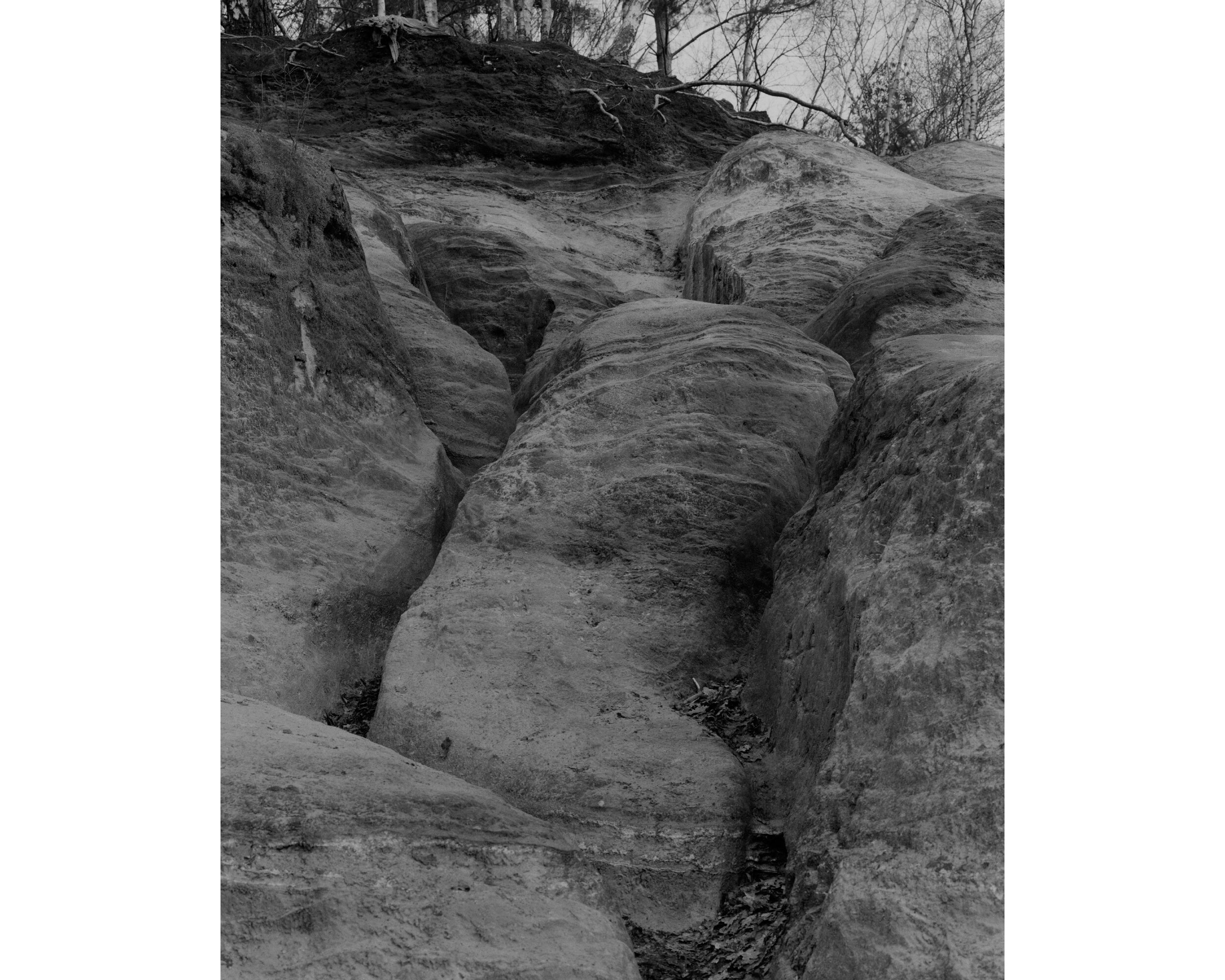

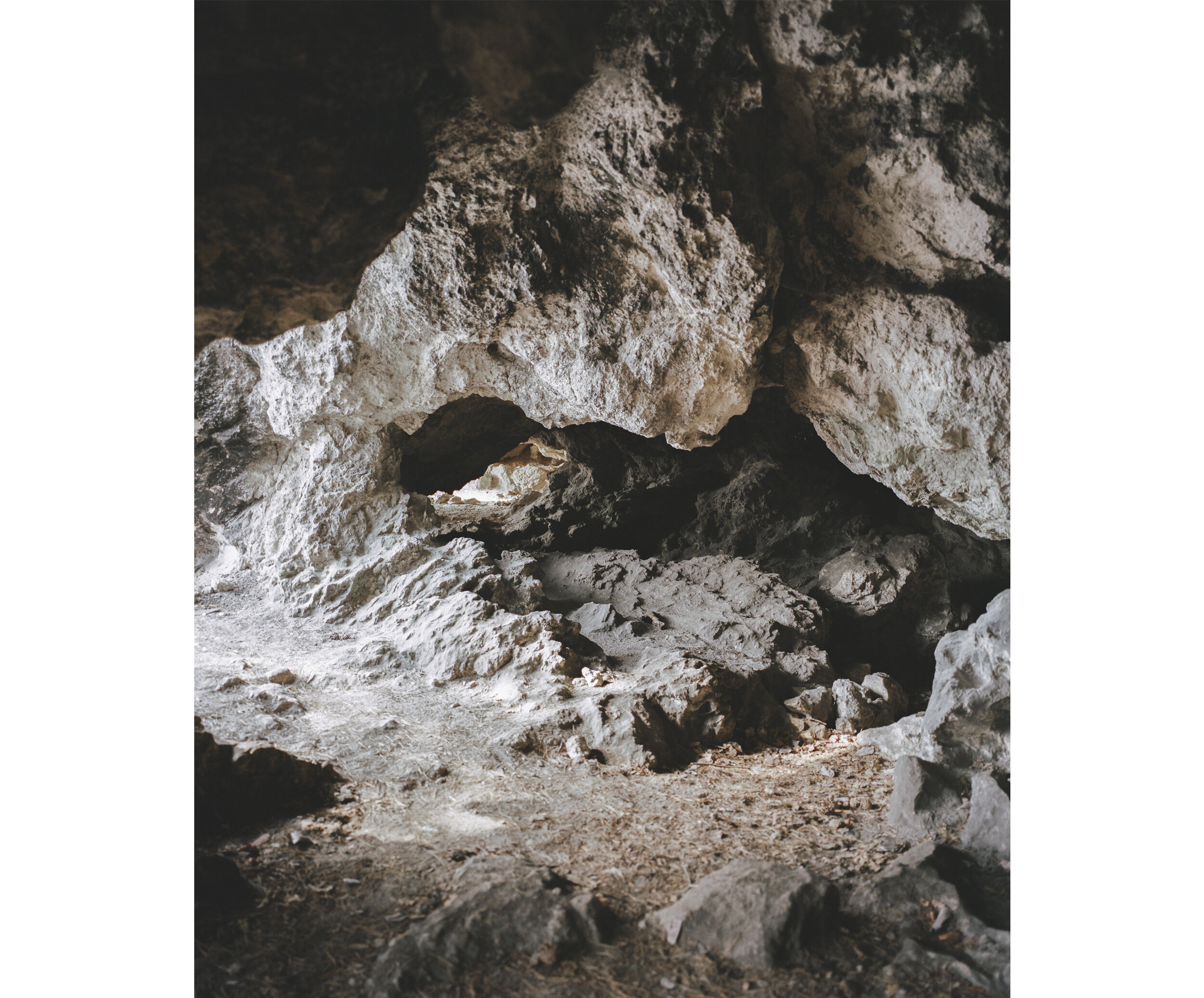

“For deep time is measured in units that humble the human instant: millennia, epochs and aeons, instead of minutes, months and years. Deep time is kept by rock, ice, stalactites, seabed sediments and the drift of tectonic plates. Seen in deep time, things come alive that seemed inert. New responsibilities declare themselves. Ice breathes. Rock has tides. Mountains rise and fall. We live on a restless Earth".

Interview by Tom Skinner

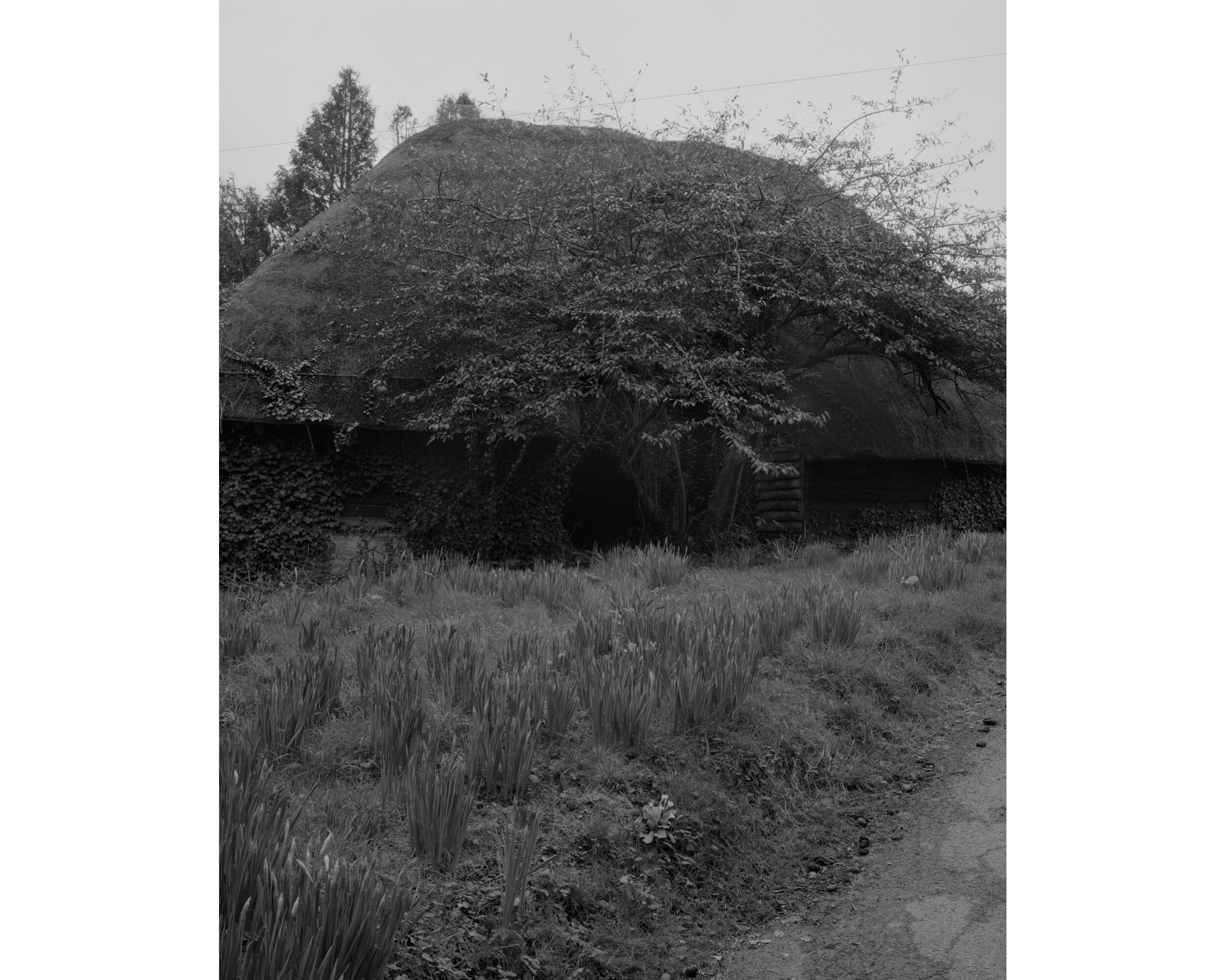

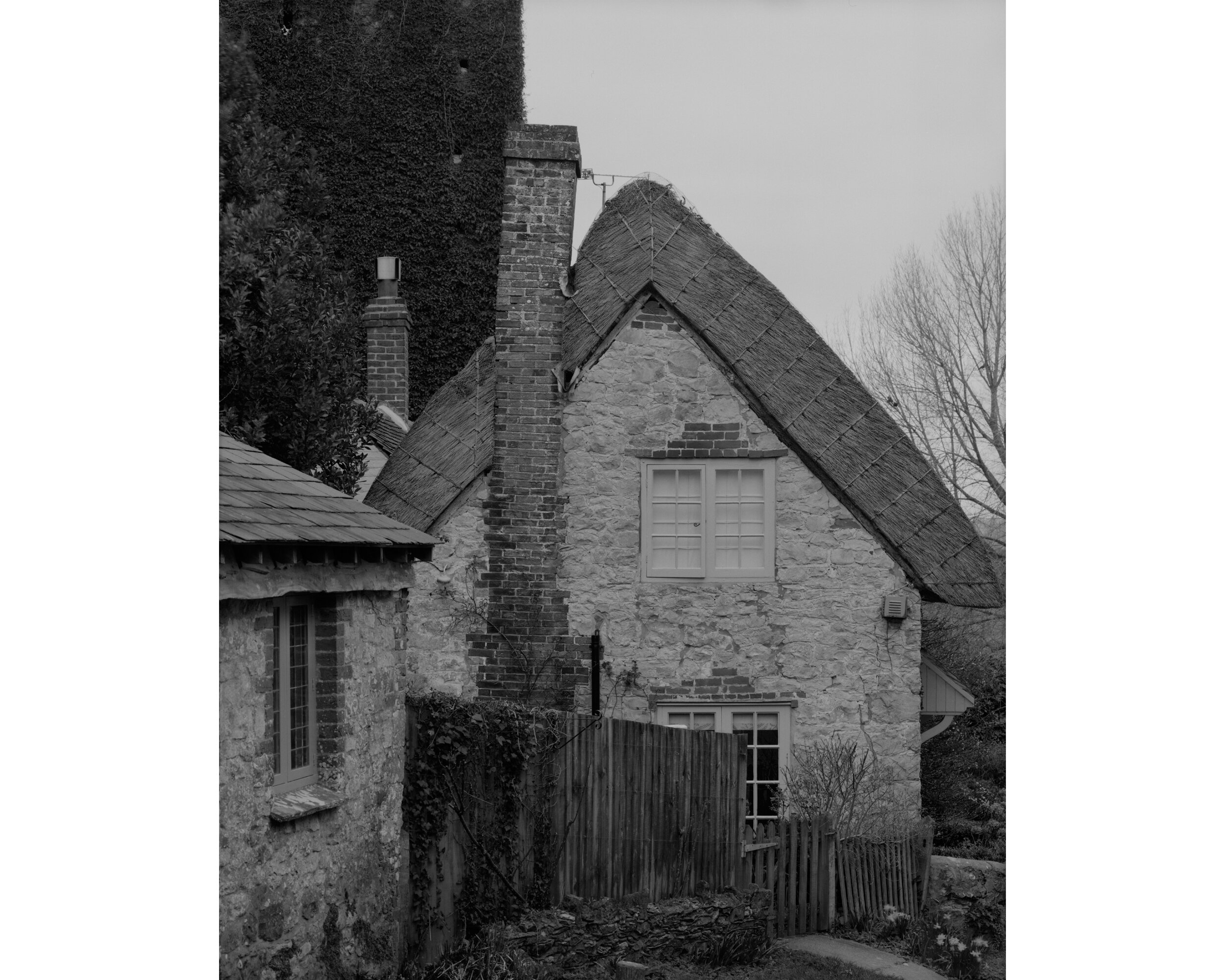

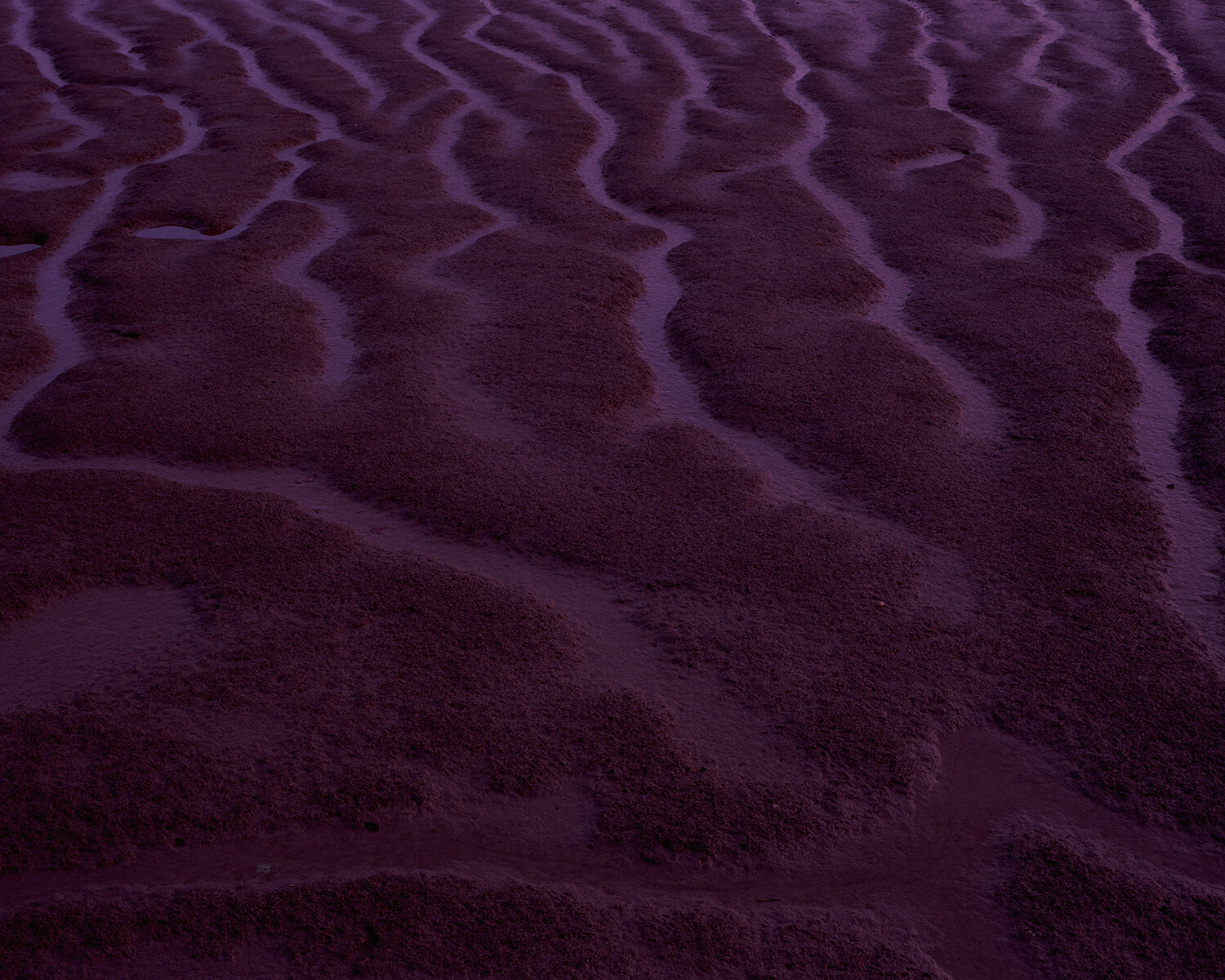

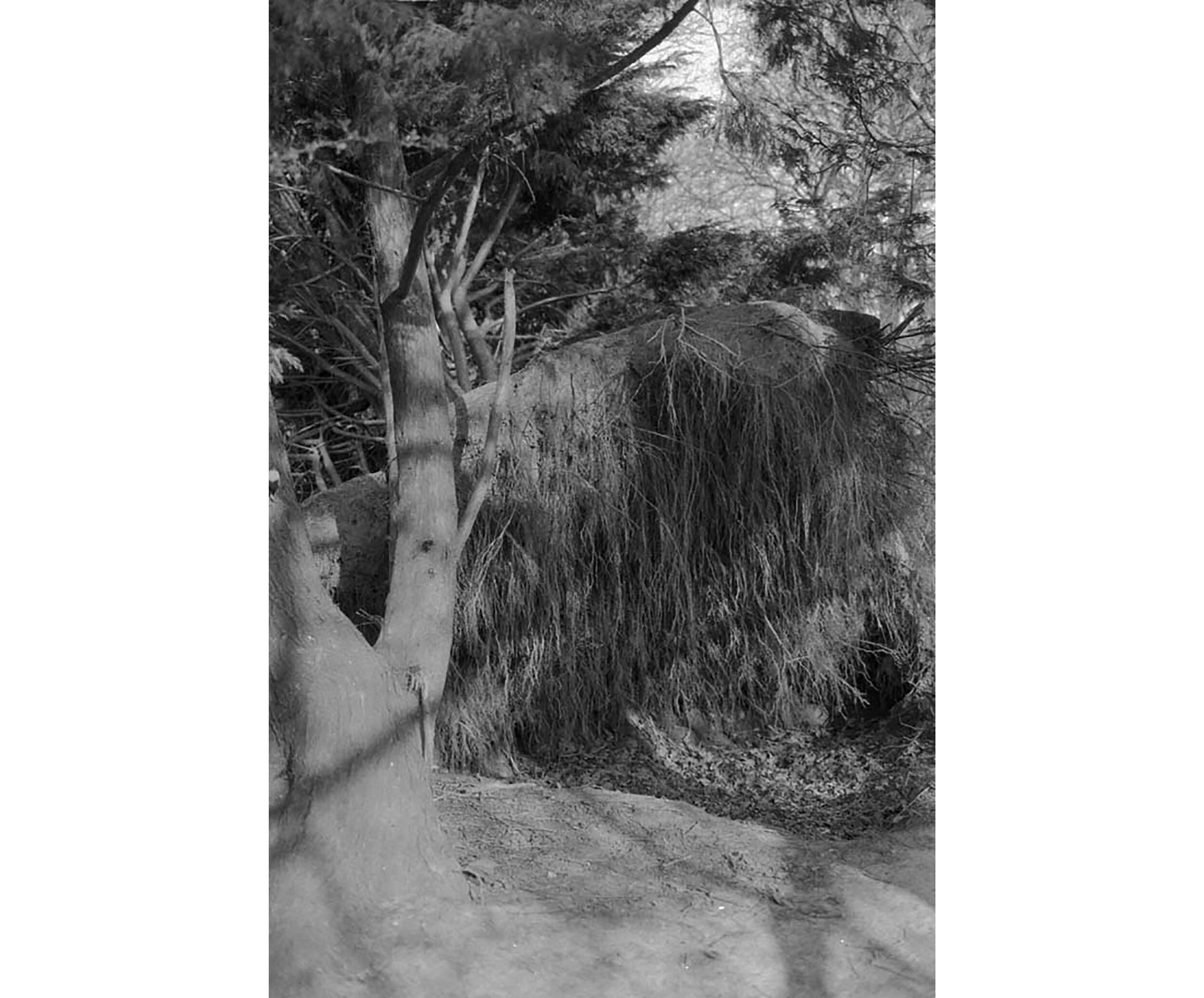

TS: Viewing the images in Locust Years, I'm reminded of the above excerpt from Robert Macfarlane's Underland, A Deep Time Journey. Particularly the images of eroded sandstone and a thatched cottage, seemingly ready to be reclaimed by the landscape. How has making this project shaped your view of our relationship with the land?

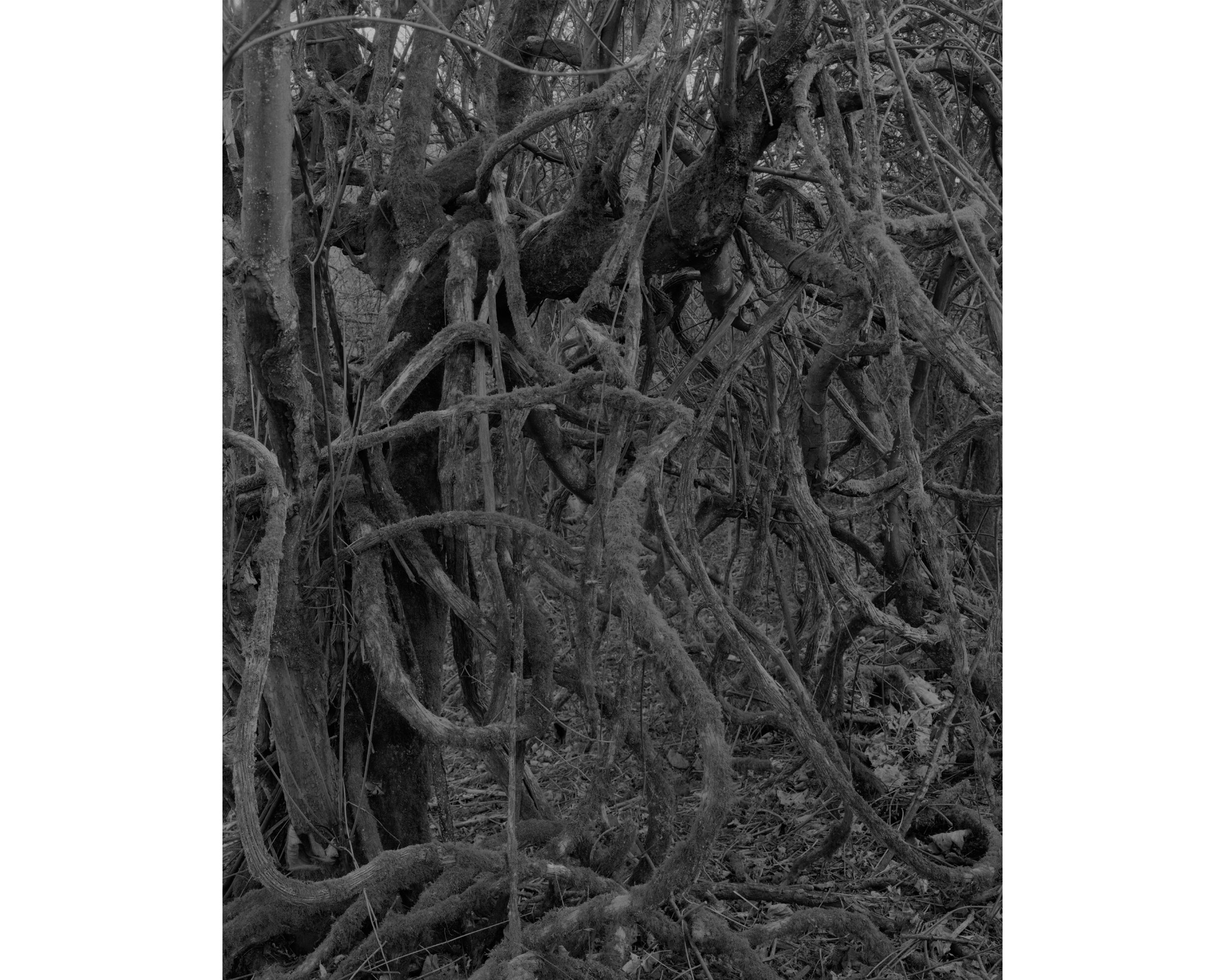

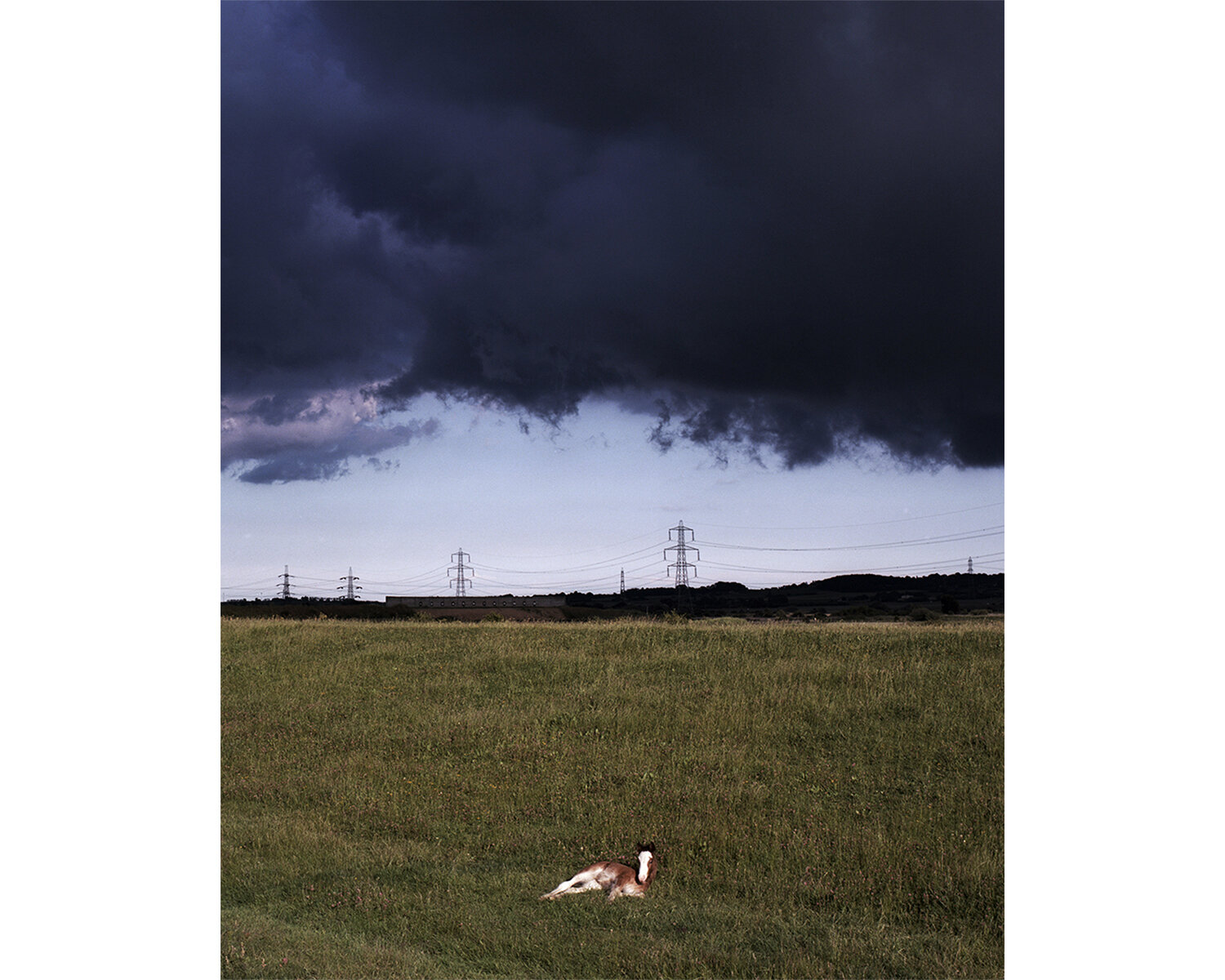

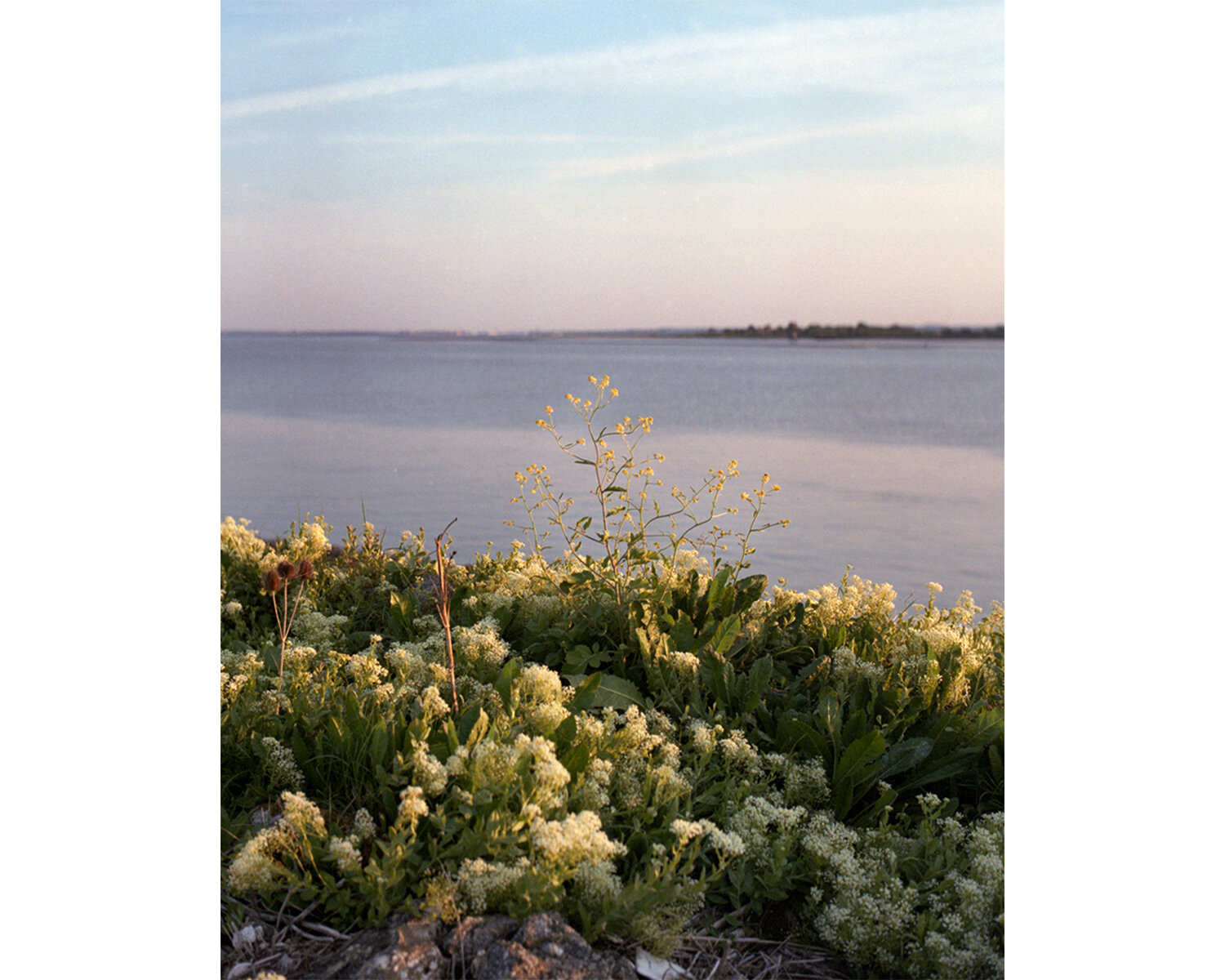

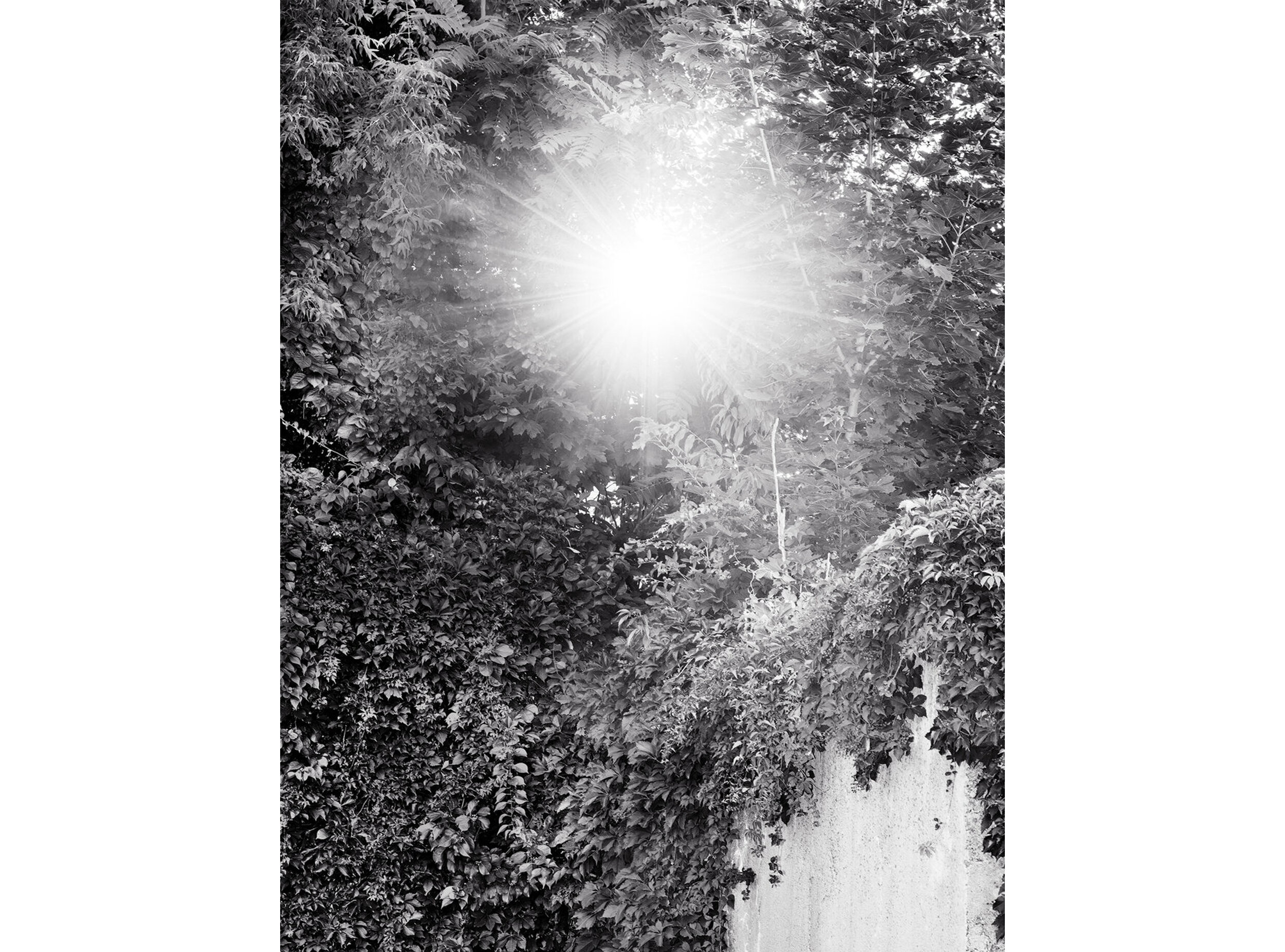

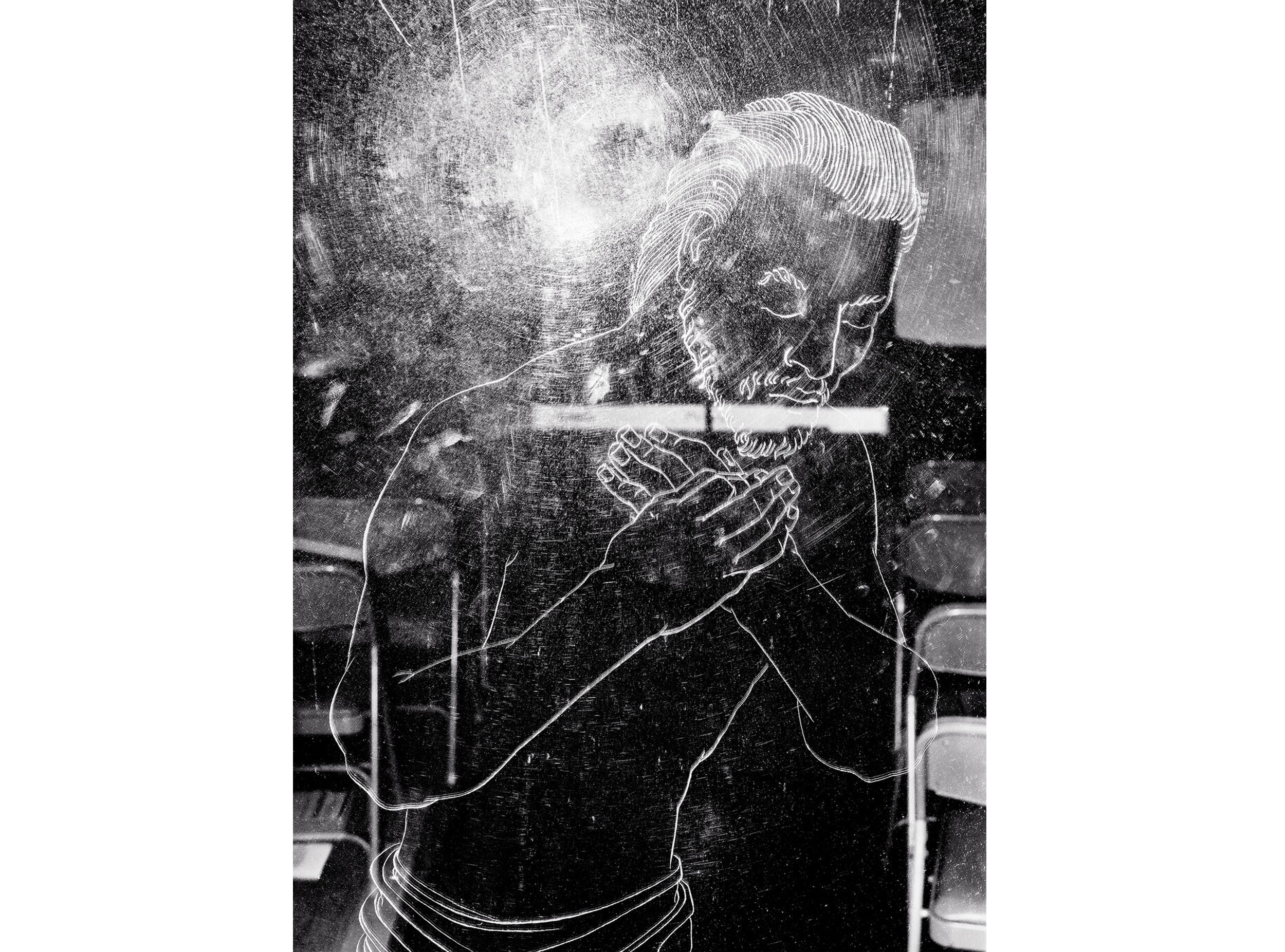

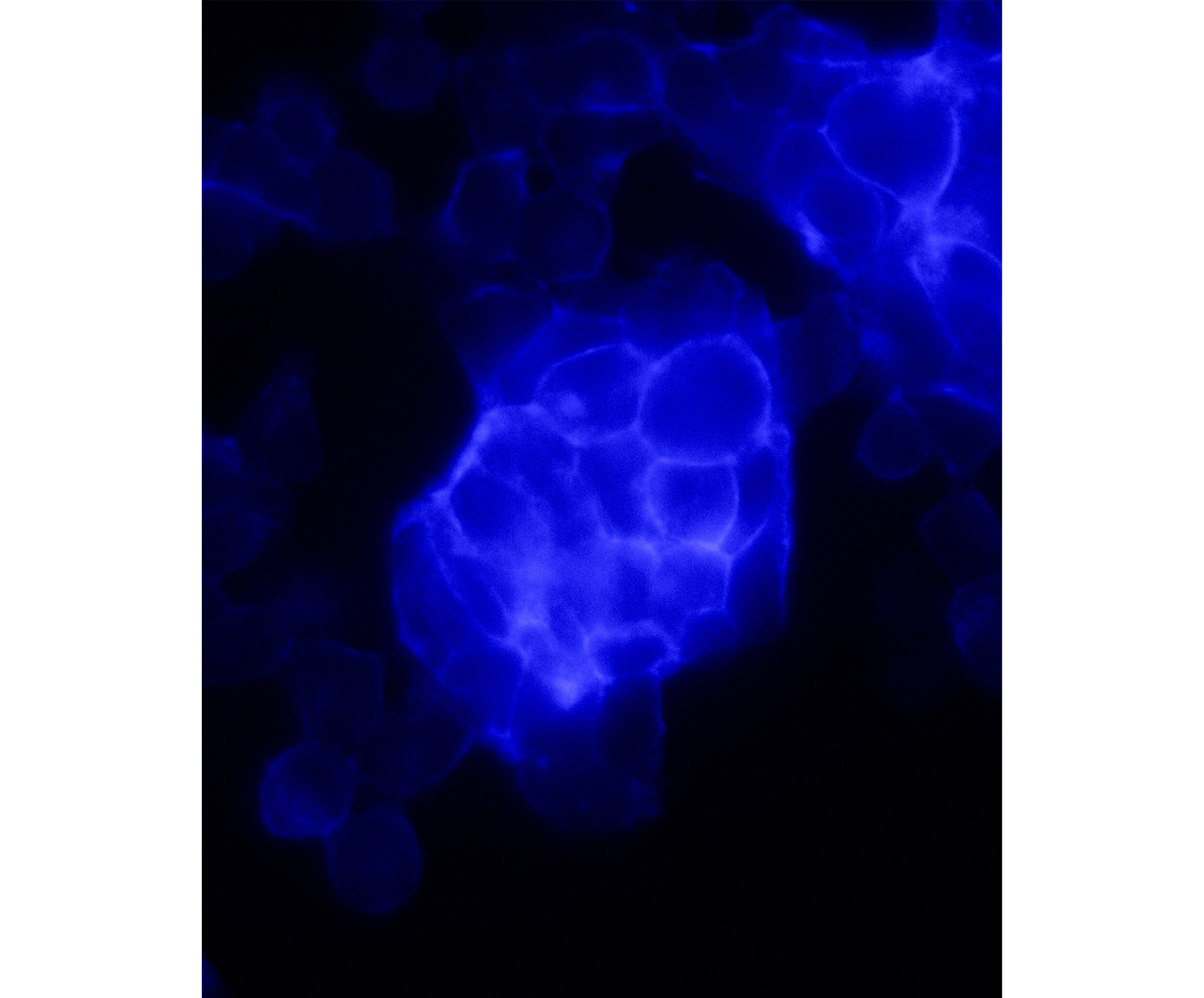

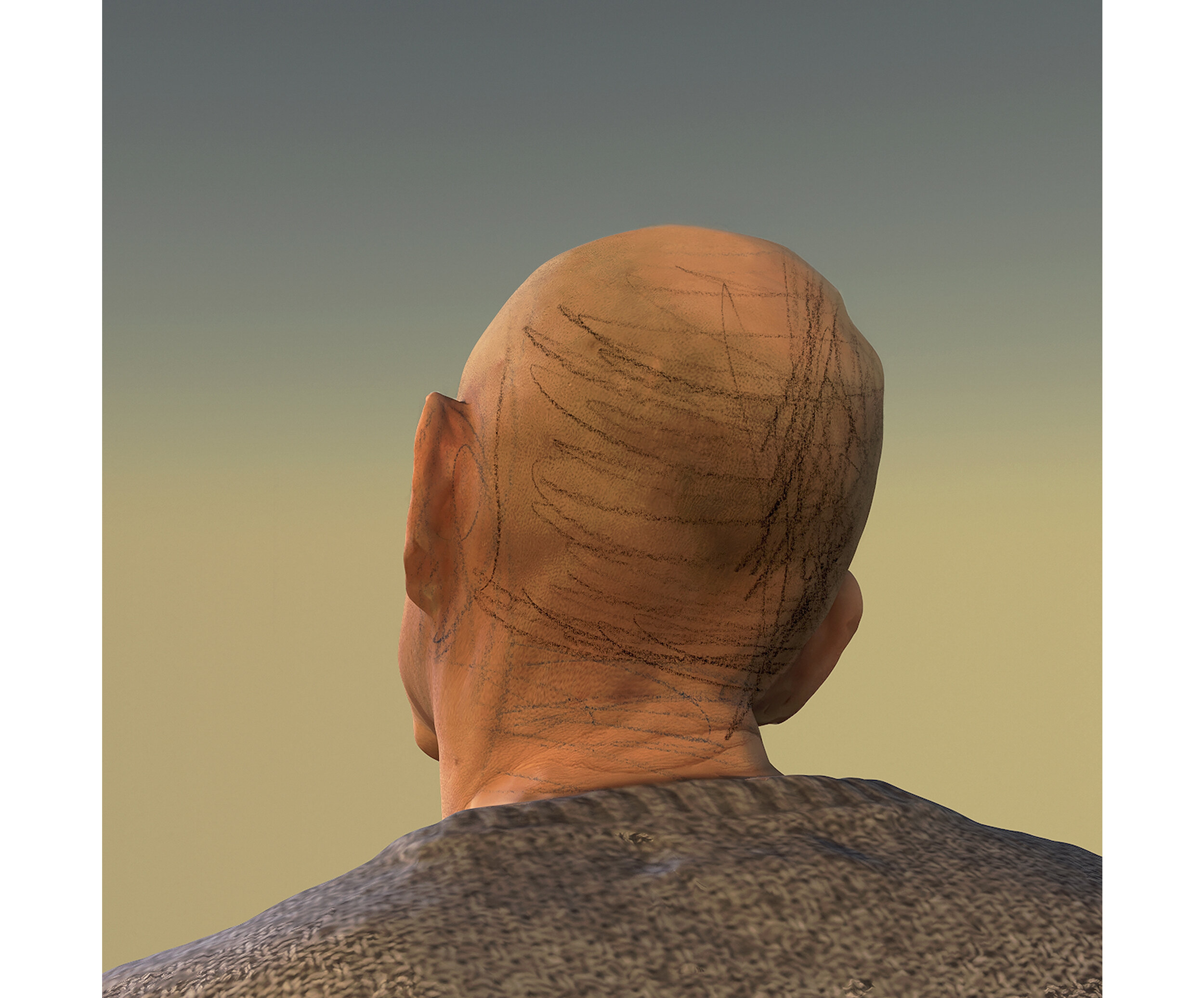

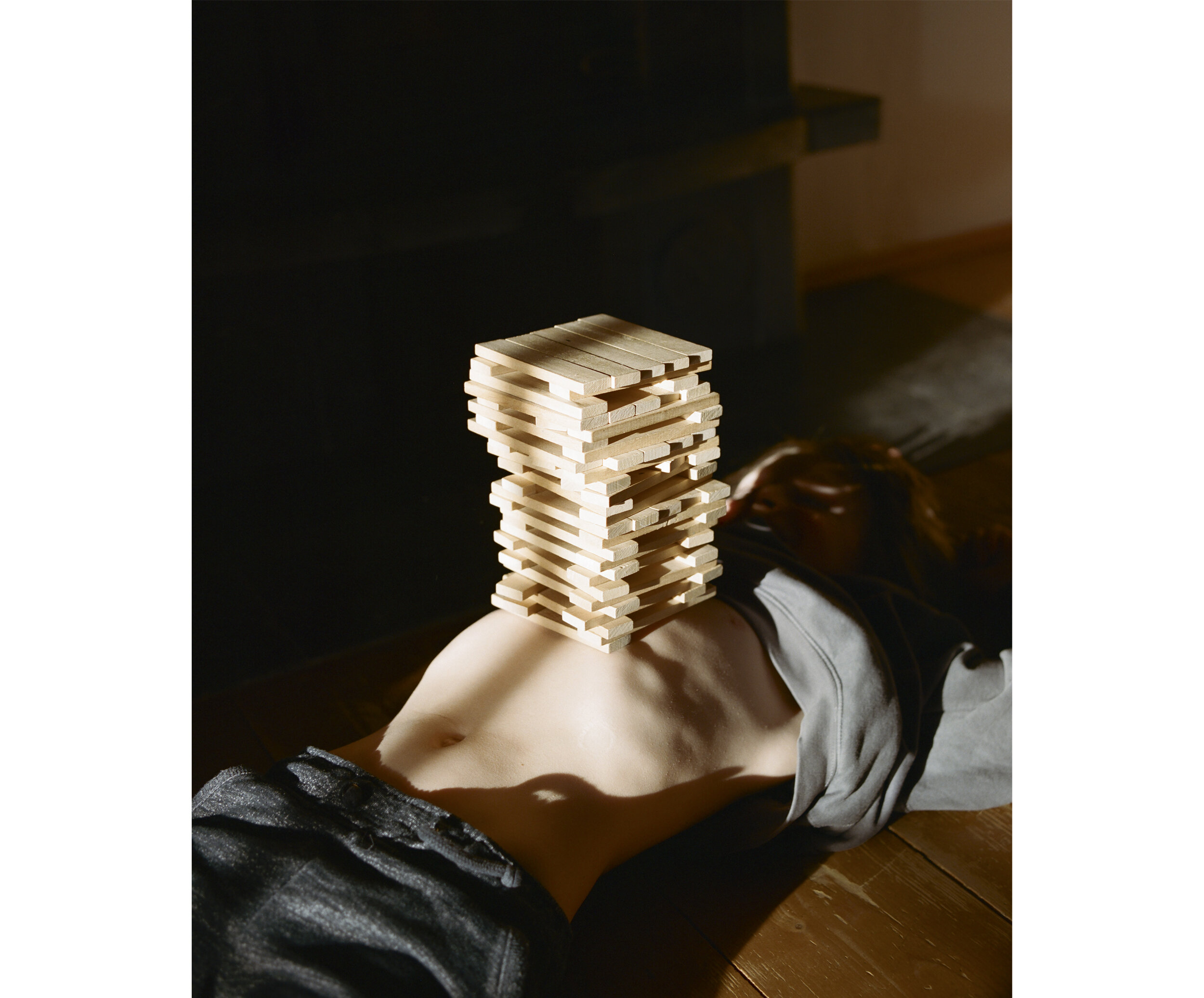

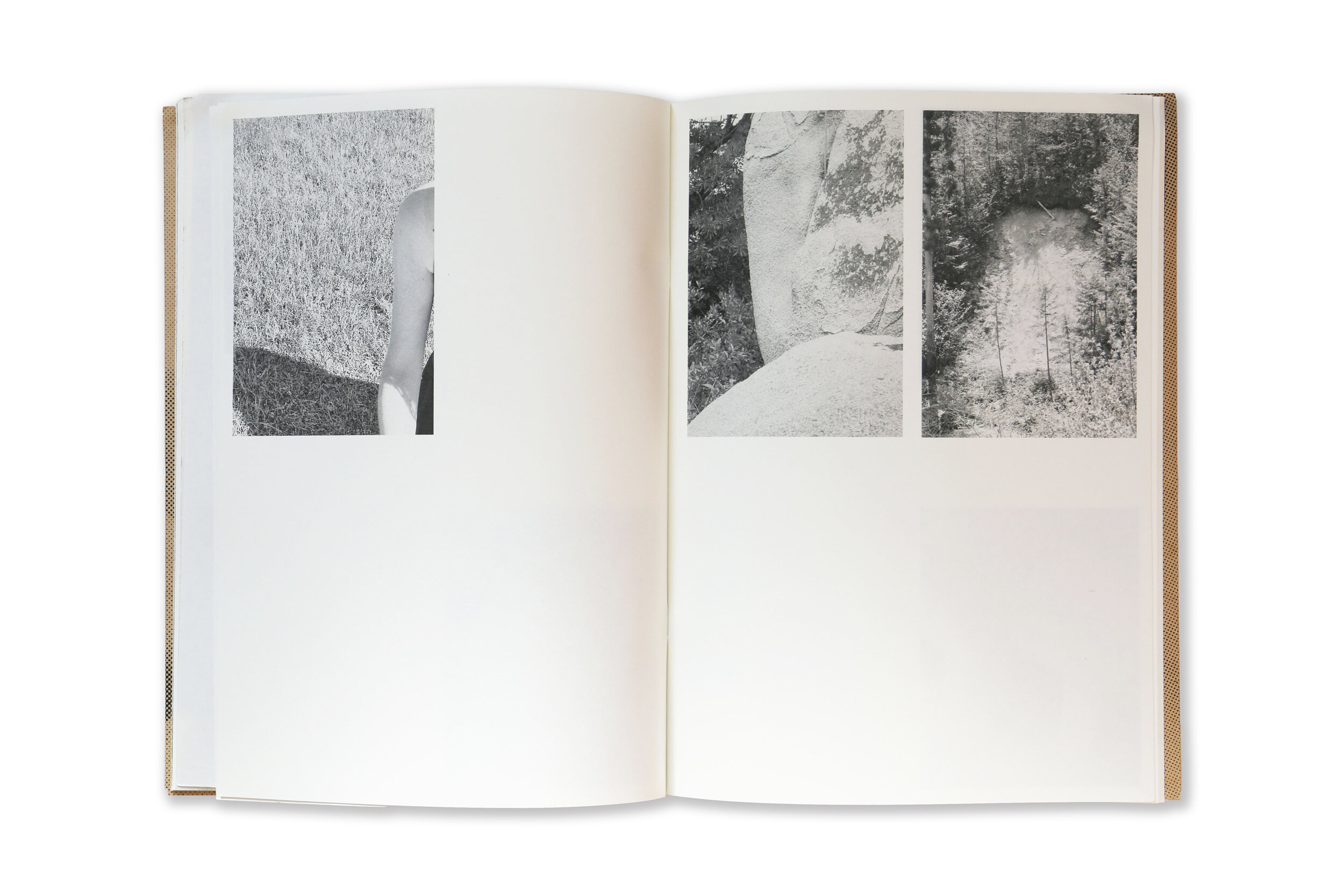

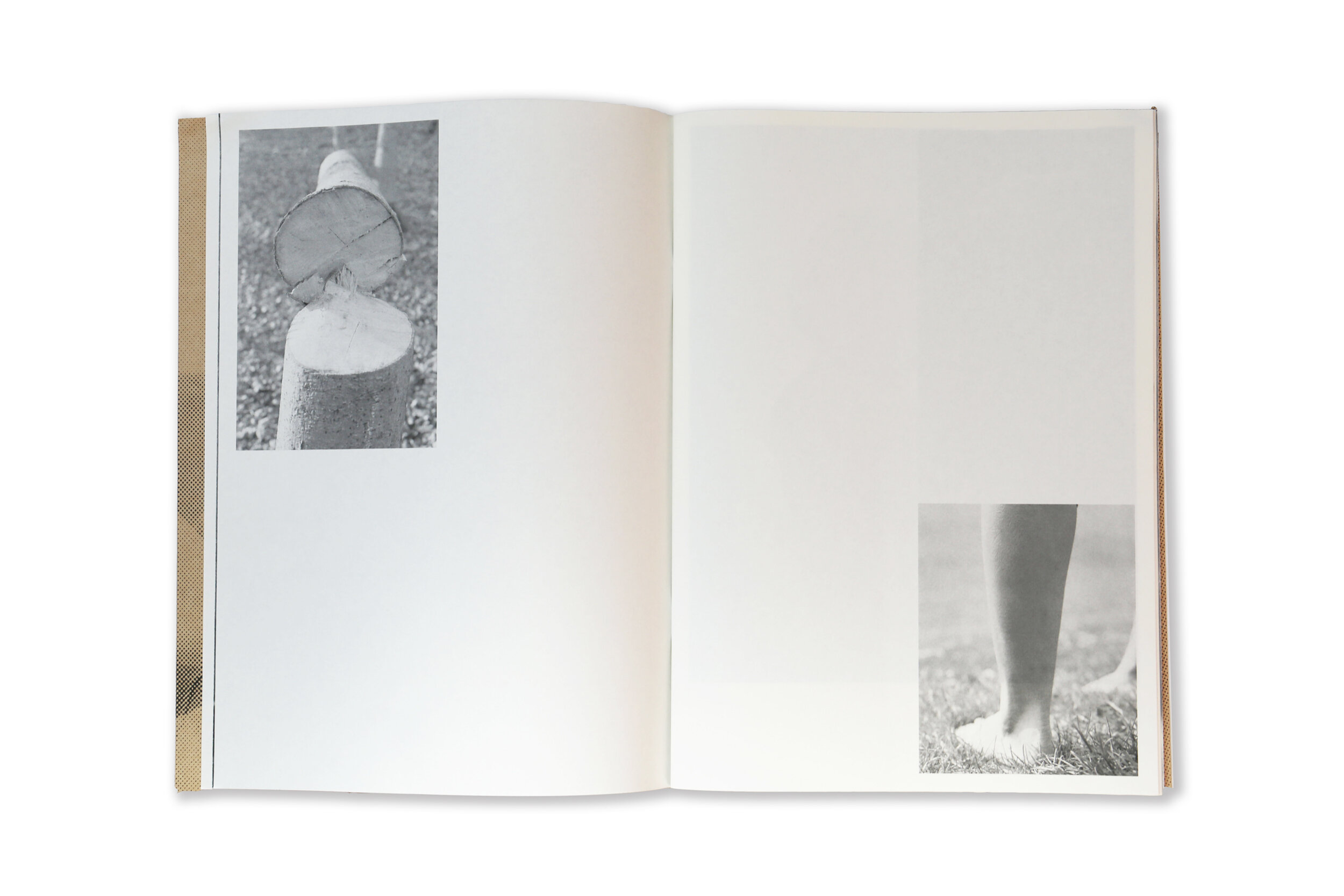

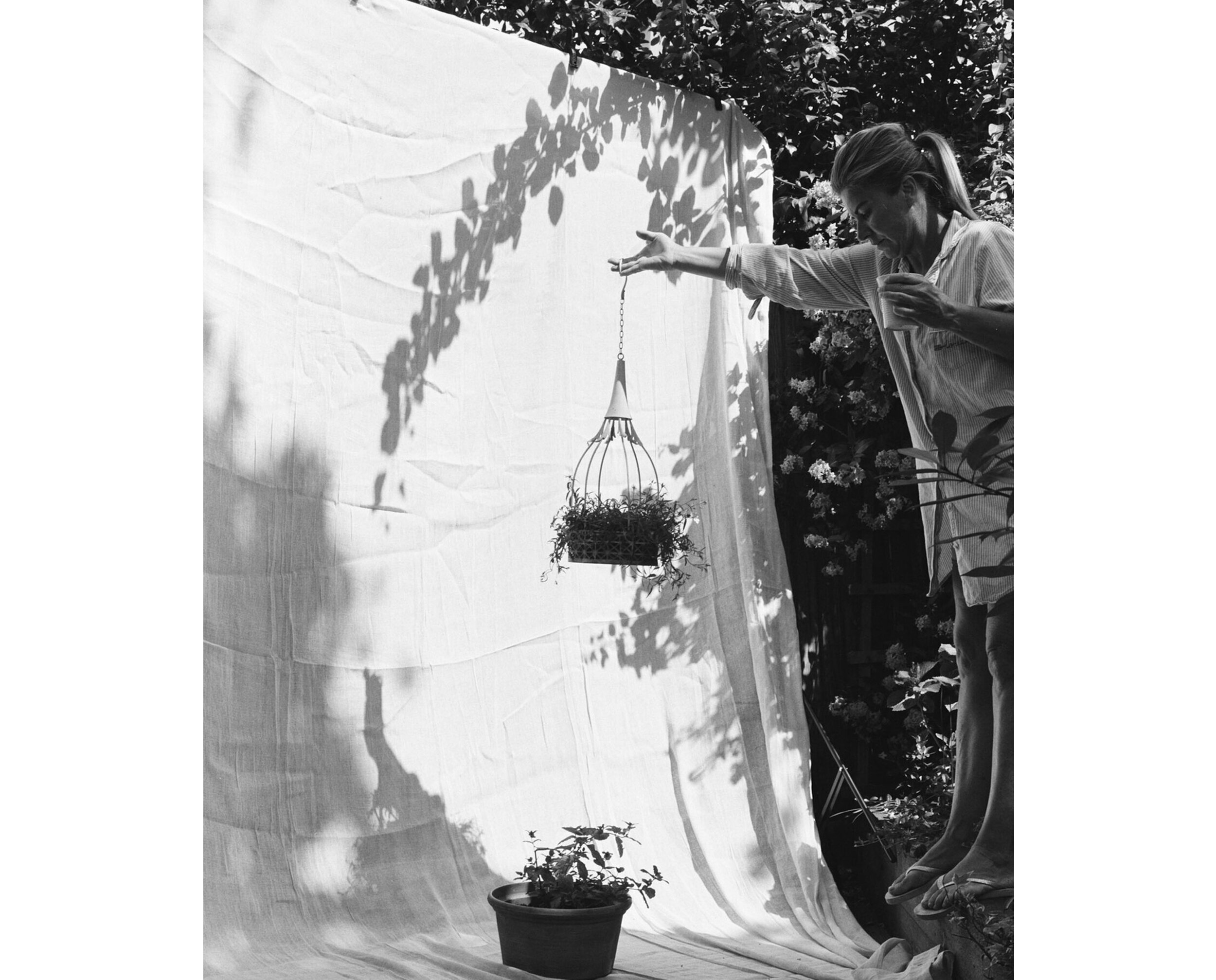

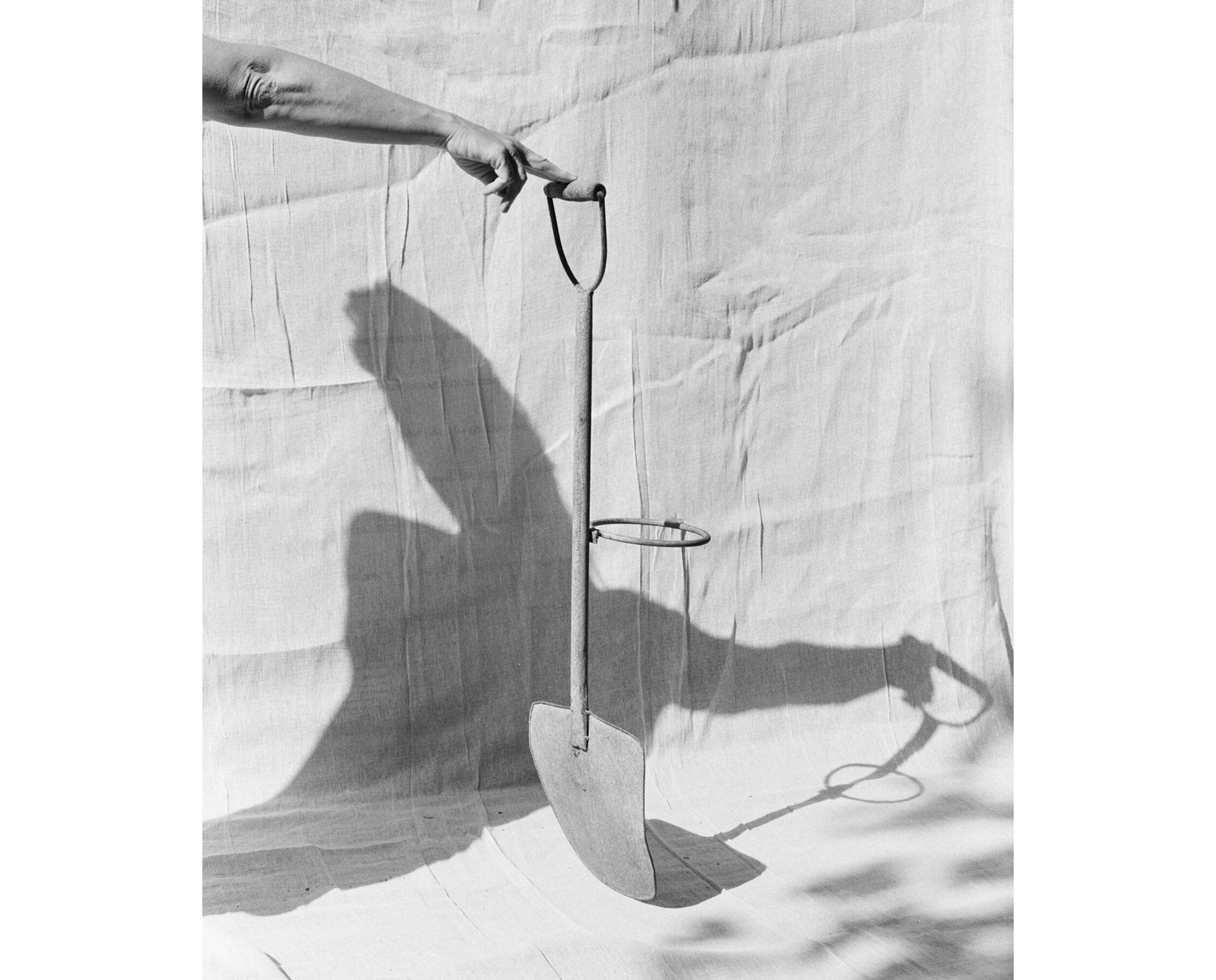

JD: Making this work I’ve been thinking a lot about entanglements of nature and culture, the patchwork of field, wood and village that define popular notions of rural England, forming the backbone to the national myth of a green and pleasant land. At the heart of this supposed harmony between humans and nature, is the idea of ‘timelessness’, the idea that things haven’t changed since a time beyond memory; how is it that this narrative has endured considering the disaster of habitat destruction and species extinction currently unfolding across the country? So I’ve been exploring how to address this abrupt disjuncture between the myth and the reality. What would it mean to reimagine the ‘timelessness’ of rural architecture, in relation to the glacial pace involved in the construction of a wood ant nest, for example, or the geological time inhabited by sandstone, the subterranean chronologies of fungi or the latent profile of a bronze age ring fort in a crop-mark. There’s a kind of eeriness in those confluences of temporal spaces that interests me, that seems to me to chime with the silent and invisible eviction of wildlife from the countryside - a spectral but ever present feature of any interaction with these landscapes in the current moment.

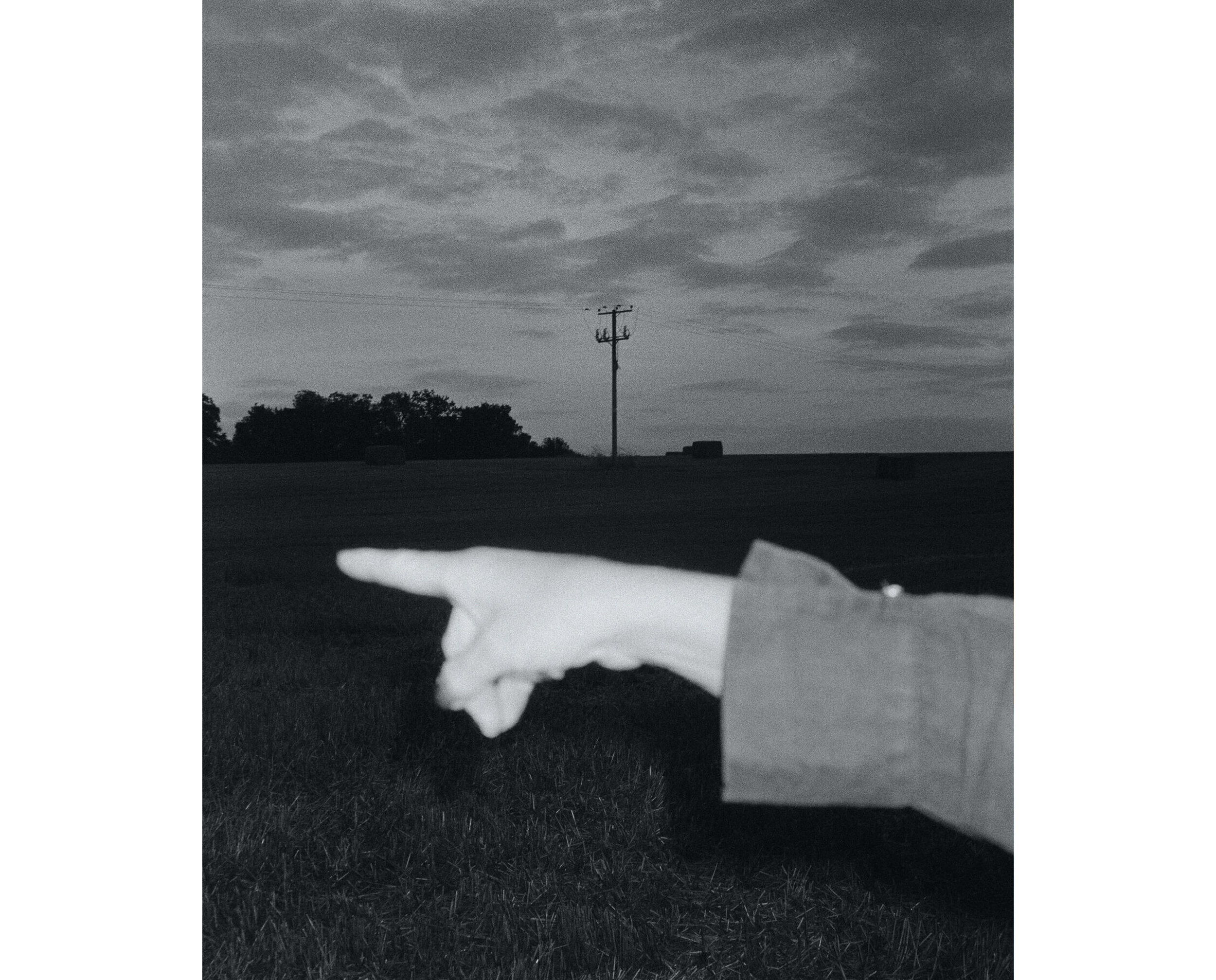

TS: Within your images, architectural forms are explored in relation to a somewhat hostile landscape, what drew you to southern England to make this work?

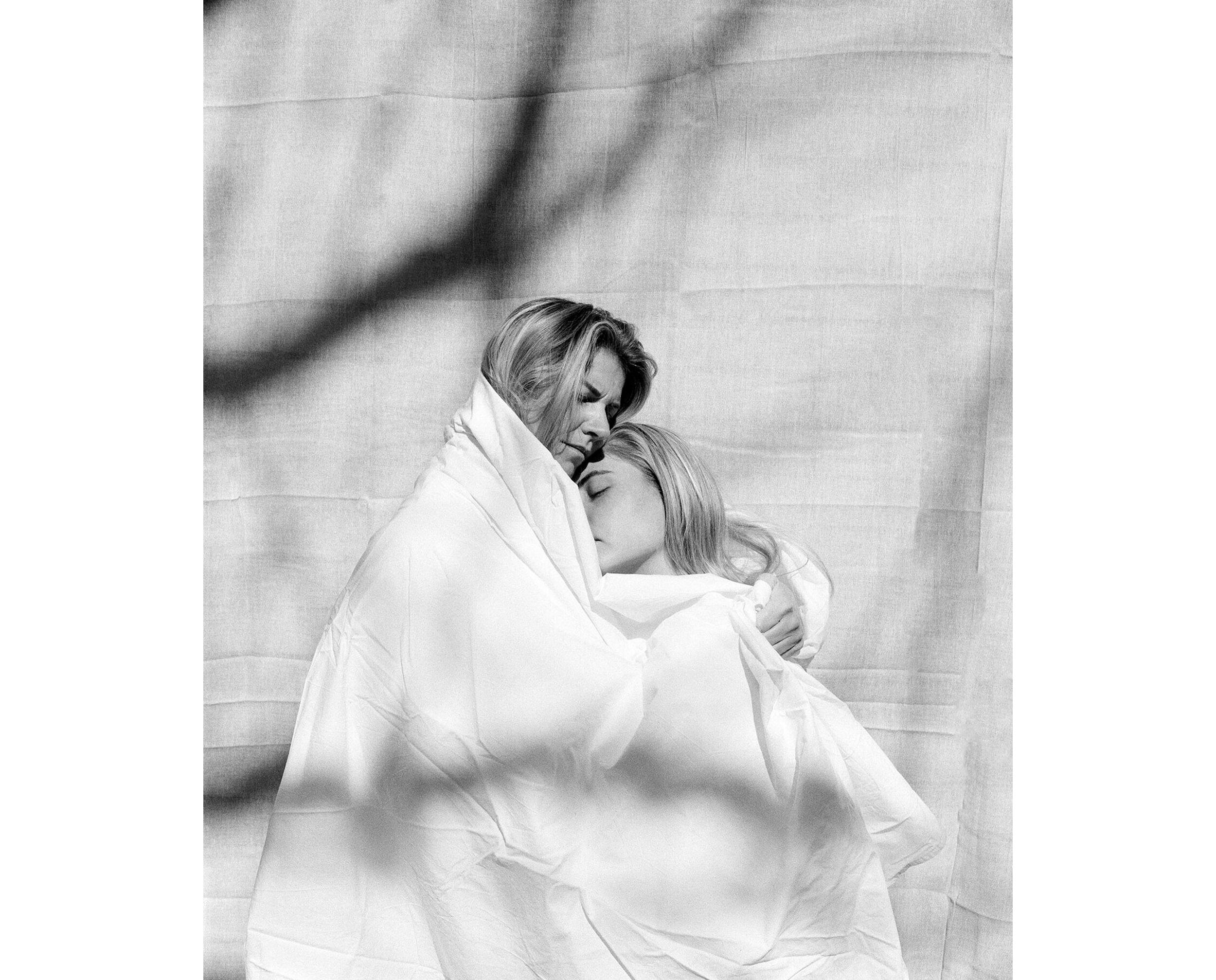

JD: I live, walk and photograph the landscape here, on the edge of the South Downs. My relationship to the place changed through walking it. I began enchanted by a landscape that superficially resembled a Samuel Palmer painting, and slowly became aware of the ancestral wealth, power and private property that are central to its history. The ways in which pasts inhabit the present moment in our experience of landscape, seem to me very pronounced here, in particular the fraught histories of enclosure and ecological destruction, or the obscene amounts of accumulated wealth that funded the building of parklands, the remnants of these practices are encoded in the land but exist alongside isolated pockets of profound beauty. There’s almost a conspiracy of silence around these facts, that manifests itself in notions of a Deep England, a kind of collective delusion - it’s this unsettling facade masking the tensions between nature and culture, and a compulsion to find some visual articulation of it, that has been the driving factor behind the work.

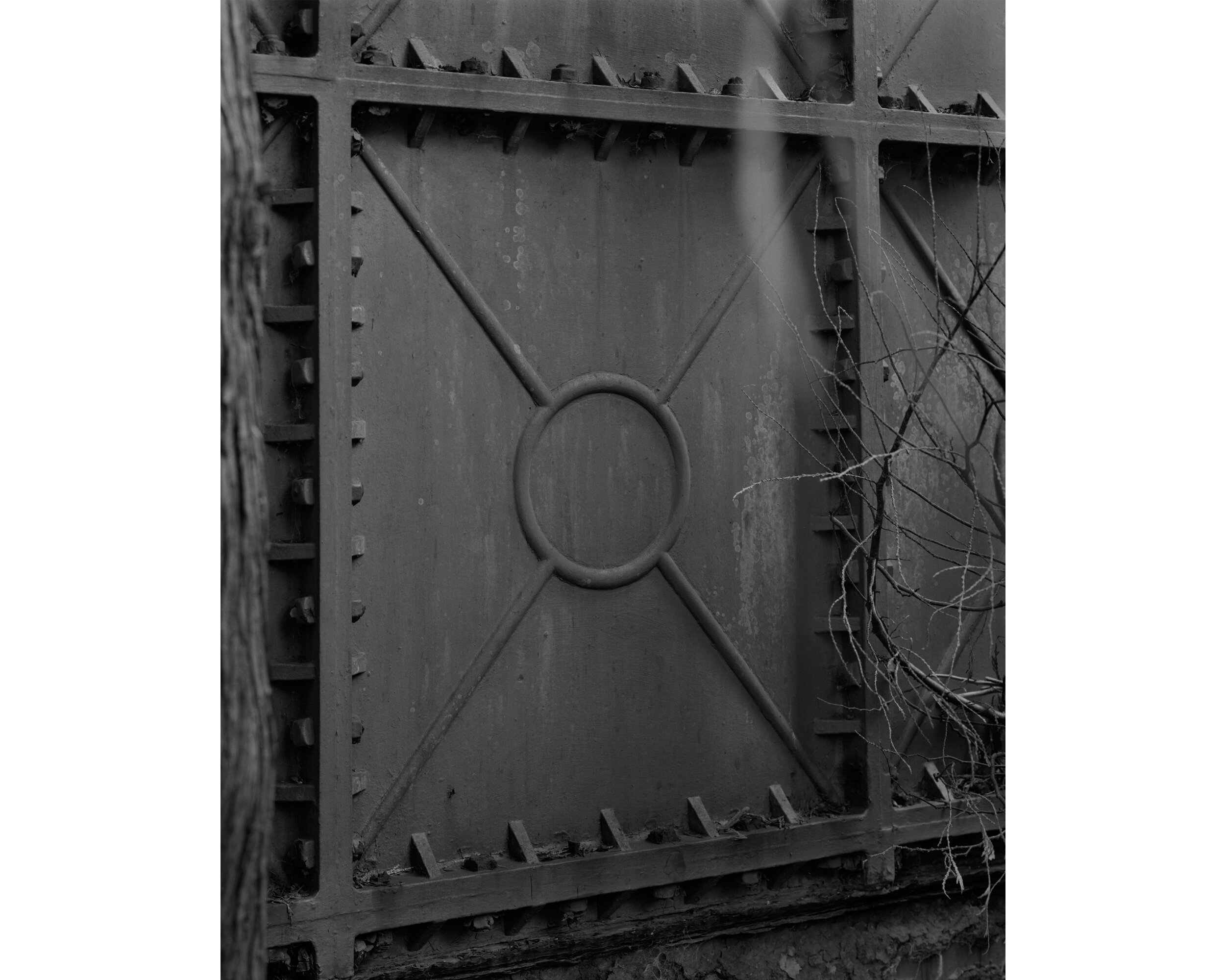

TS: Thatched cottages, relict machinery and churches seem a world away from the ecological crisis which is presented in mainstream media; global warming and single-use plastics for example. Can reframing our relationship with the planet in a more familiar and perhaps timeless setting provide a new way of thinking about ecological crisis?

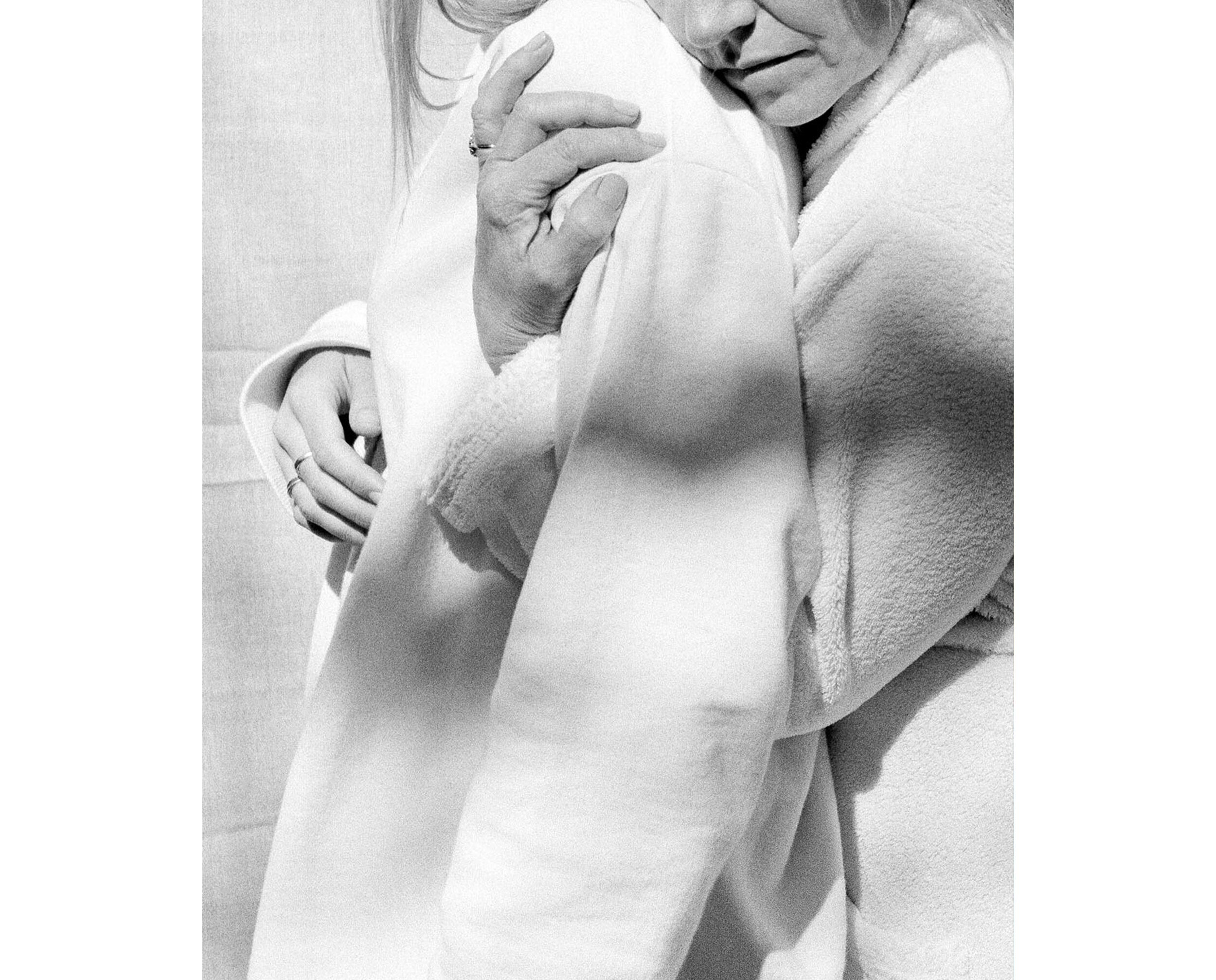

JD: Yes, I think so, depending on what stories we tell. The architectural forms present in this work are products/cultural symbols of a social order that has been central to the configuration of the English rural landscape, but also to the consolidation of land and power that has estranged people from their own land and deprived them of meaningful experiences with nature. Richard Mabey speaks of the ideal relation to the more than human world as having ‘a sense of neighbourliness…based on sharing a place, on the common experience of home and habitat and season’. Climate is only one half of the story here - the ecological crisis which has seen 60% of the worlds wildlife destroyed since the 1970s has been enabled in part by its own invisibility, but surely also because we just haven’t cared, or had the knowledge to identify the ongoing destruction wrought on our own doorstep by soaking the countryside in chemicals, among other destructive practices. So it is important to reimagine the dominant narratives and myths that shape our relation to the countryside, to the local - you only have to look on Google maps at the closest area of undeveloped land to where you live and you’re likely to find the shadow of an old hedgerow ripped out.

Rustgill

Relict Pollard

TS: Specific species of trees, plants and fungi are photographed and identified throughout the series, do any have particular meaning to you personally, or within the context of your work?

JD: The organisms depicted are ones that confound, obscure and beguile in some way or another, characteristics at odds with those that our countryside has traditionally favoured; predictability, order, innocence. The early spider orchid, for example, is a mimic - it deceives a particular species of bee into attempting to mate with it, in order to spread its pollen.

TS: Do you have a prediction (or perhaps hope) for the future of the English countryside?

JD: This work comes from a place of unease, but I hope for better access, more community ownership of land, more land managed for nature rather than profit. This would be a good place to start.